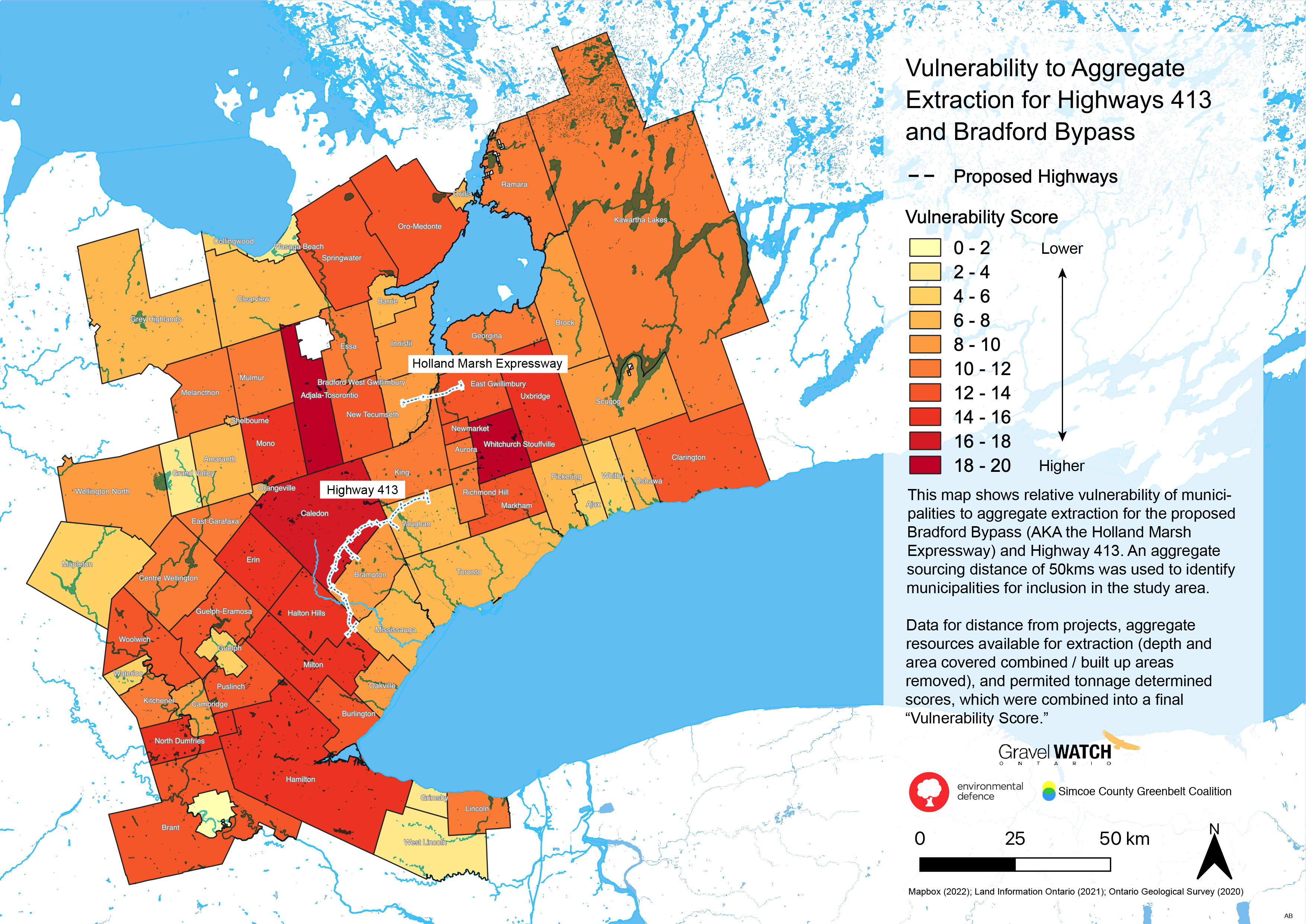

This choropleth map is segmented by municipality, and weighted according to a scoring system that combines four scores:

- “PER_SCORE”, which is the percent of the municipality’s area covered by sand and gravel resources, excluding built up areas;

- “DIST_SCORE”, which is a measure of the distance that the municipality is from the respective projects;

- “TON_SCORE”, which is a measure of the total tonnage allowed in the municipality;

- and “DEP_SCORE”, which is a measure of the depths of the sand and gravel resources contained within the municipality.

PER_SCORE

For the PER_SCORE the sand and gravel mapping, which were separate files, were combined, the built up areas in the municipality were then subtracted from the combined file, and the result was then measured as a percent of the total area of the municipality. Scores are from 1 to 4, representing 25% increments.

DIST_SCORE

The distance scores are derived from the 20 kilometre and the 50 kilometre distances from the proposed projects. The 50 kilometer radius from the projects is based on a conservative estimate, provided by Gravel Watch Ontario, of the distance from which aggregate resources are normally sourced for projects, with that distance sometimes being expanded outward to 70 kilometers. A score of 2 was given if the municipality was within the 20 kms radius, and 1 if it was within the 50 kms radius. For municipalities within the 20 km radii of both projects a total of 4 was given, and likewise, if a municipality was within the 20 km radius of one project and the 5 km radius of another, it got a score of 3.

TON_SCORE

The tonnage score is based on a decile, with municipalities receiving a score of between 1 and 10, where 10 represents the highest total tonnage permitted within the municipality.

DEP_SCORE

A depth score of aggregate resources based on mapping by the Ontario Geological Survey (OGS) was included to give an additional metric of impact. Depth data are provided by OGS in four categories: Less than 1.5m; 1.5m to 3m; 3m to 6m; and Greater than 6m. DEP_SCORES were apportioned from 1 to 4, with 1 for 1.5m and 4 for Great than 6m.

Sources

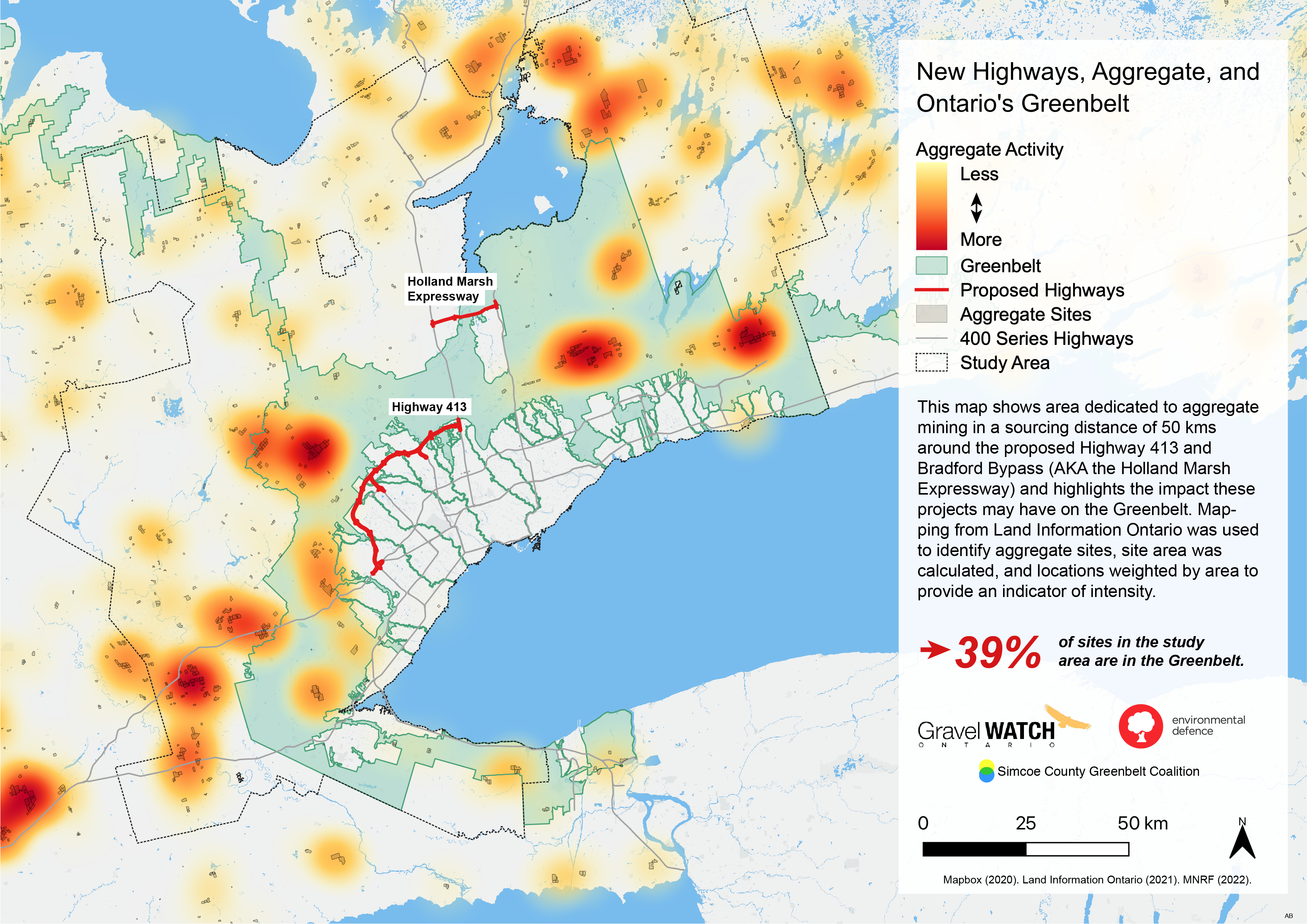

“Aggregate site authorized – active”, Land Information Ontario. Info updated November 16, 2018. Data updated December 15, 2021. Downloaded November 25, 2021. (Link)(Data)

Aggregate Resources of Ontario—2020”,Ontario Geological Survey. Downloaded June 30, 2021. (Link)

“Greenbelt outer boundary”, Land Information Ontario. Info updated August 6, 2021. Data updated May 18, 2017. Downloaded January 2, 2022. (Link)

“Mapbox Base Monochrome”, Mapbox (personal account). Created January 10, 2022. Accessed January 11, 2022. (Link)

“Ontario Road Network (ORN) Road Net Element”, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. Info updated September 27, 2019. Data updated January 5, 2022. (Link)

“GTA_West_RevisedRoute_August2020_Lat_Lon”, Environmental Defence/As The Crow Flies Cartography. Received November 30, 2021.

“Municipal Boundary – Lower and Single Tier”, Land Information Ontario. Info updated June 4, 2019. Data updated April 20, 2021. (Link)