Introduction

Cars.

They are central to our lives. They serve as the main mode of transportation for most of us, enabling us to travel to work, to shop and visit amenities, such as restaurants or movie theatres, as well as ferry our children to and from school. We plan vacations around them, plotting routes that can span the continent.

We also spend a huge amount of money on them.

When something is as integral to our lives as cars, its ubiquity tends to obscure its impact and how, in reality, it is far from normal. To the extent this veneer of normality obscures that impact, it is difficult both to understand its outsized role, and to imagine a world in which that role is either less or different.

This Issue Brief dives into the data on cars, the resources they consume, and the role they play in our every-day lives.

The Financial Burden of Car Ownership

Much like the infrastructure supporting cars, costs that go towards owning and operating a vehicle have been thoroughly normalized. We have well-established systems and processes that help people purchase a good that costs, on average, $45,000, with little more than a decent credit history and some semblance of future income surety.

Car payments are, generally, routine, and barring unexpected mechanical issues, our monthly income tends to cover them.

But, break the figures of car ownership down a bit, and their cost starts to seem more of a burden than a run-of-the-mill item on the household budget would suggest.

A recent study by the Canadian Automobile Association estimates that, on average, Canadians spend between $8,000 and $13,000 per year on their cars.

That figure alone raises the question of what you could do with $8 to $13 thousand dollars at the end of the year. A year’s post-secondary tuition? An extended stay at a villa in the south of France? Plow it into savings or investments for early retirement?

The Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) provides a better understanding of what this overall amount comprises.

Total Cost of Ownership

TCO incorporates the purchase price or lease payments, depreciation, insurance, fuel, maintenance or repairs, taxes and fees, financing costs, as well as ancillary costs such as parking and tolls.

Using averages for respective categories in Canada, the TCO for a car looks something like this:

Now, comparing this amount to the average annual income in Canada, which is just shy of $60,000, shows that many Canadians are spending roughly 21% of their gross earnings on car ownership. Net income, of course, would raise this figure a few points.

According to the folks at Investopedia, costs associated with transportation should be no greater than 10% of one’s salary.

Cars, a House, or Early Retirement?

The costs outlined above are, for the most part, directly related to the operation of a single vehicle. Expanding the calculation to the lifetime of a car owner, who owns and operates a small car over the course of a 50-year span, and incorporating social costs, such as that of infrastructure and pollution, and the cost skyrockets to an astonishing $930,150, of which society pays roughly $371,250.1Figures provided in the Forbes article were updated to reflect current amounts in CAD.

That’s the cost of a house, or a significant portion of a retirement plan. Most damning, though, is the fact that this is an amount paid for something that sits parked and unused 95% of the time.

These costs are gross, though, and likely provide a too simplistic accounting. Viewing net costs would account for portions that return to society, such as salaries to autoworkers and research and development spending by auto manufacturers. The point remains that car ownership is a significant long-term expense, often requiring individuals to forgo other opportunities, such as homeownership or early retirement.

Social and Environmental Costs

Economists use the term opportunity costs to question what might be lost when a particular course of action is taken. The missed opportunities for buying a house or saving for retirement, noted above, are examples that bear a direct relation to the individual, but they also filter through the economy in some pretty significant ways.

The conversation around affordable housing doesn’t often account for the high cost of car ownership, and many of the solutions offered by the likes of our Premier, such as building more housing supply in sprawl-style developments, in fact hinge on car use. These are communities designed in such a way that residents are unable to access basic amenities, not to mention getting to places of employment, without getting in a car and driving.

The more that we design our communities around cars, the more we lock ourselves into the trade-offs, or the opportunity costs, that come with that form of land-use.

Paving over land for roads, for instance, while facilitating a certain amount of economic activity, also means that that land is no longer available for other uses, such as housing or growing food or sequestering carbon.

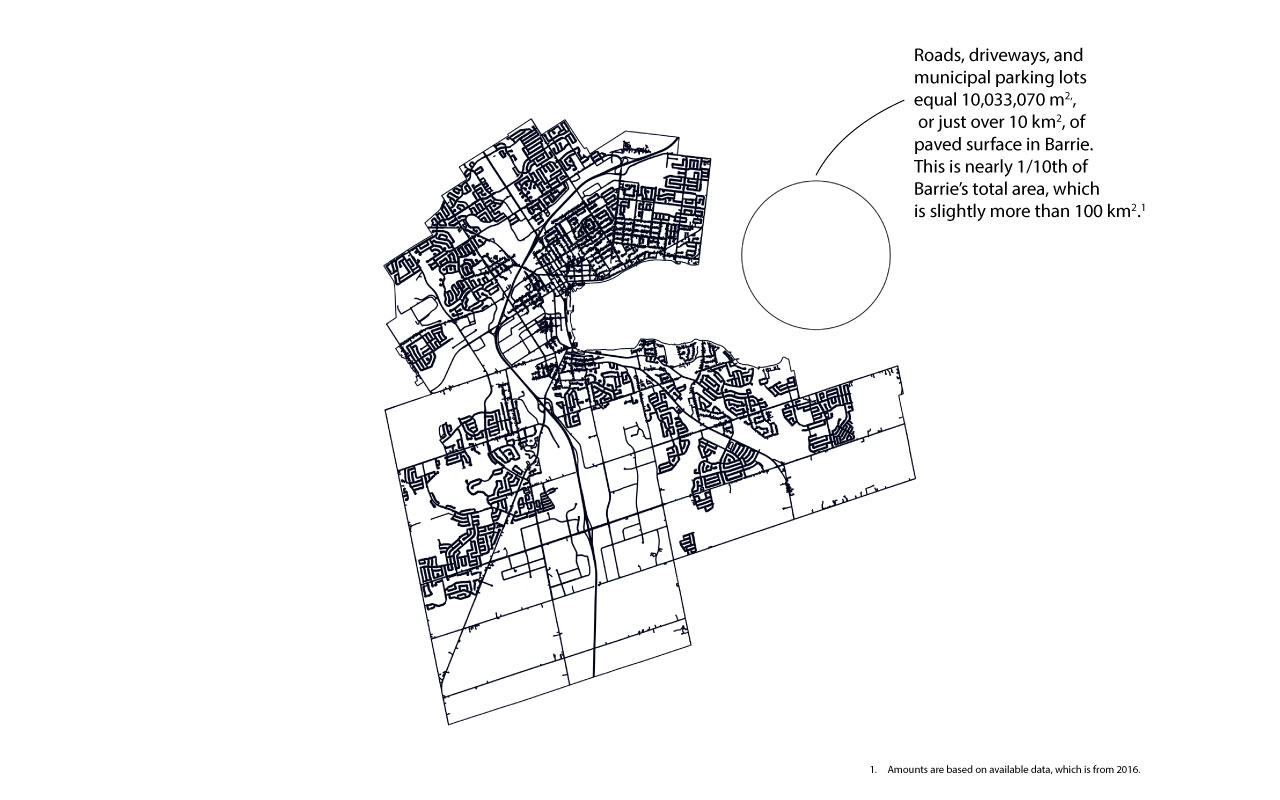

To illustrate this, if all the paved surfaces in Barrie were bunched together, it would form a fully paved parking lot over 10 km2 in size.2Data available for this map doesn’t include private parking lots, such as those outside of grocery stores.

In terms of the amount of housing that could be built in an area of that size, at Barrie’s current average density, which is slightly less than 15 people per hectare, this would provide enough space for an additional 5,742 average sized households, or an additional 14,930 people.

Barrie’s Official Plan, however, calls for a density target of 150 people and jobs per hectare in the Urban Growth Centre, an area covering 156 hectares around the lakeshore. At that density, 10 km2 provides enough space for an additional 42,000 units, nearly double the goal of 23,000 units built by 2031. (Ultimately, with a population forecast of 298,000 for 2051, Barrie’s overall density is likely to be around 30 people per hectare.)

In terms of natural productivity, 10 km2 of prime farmland could produce, on an annual basis, around 10,000 tonnes of corn, or 3,500 tonnes of soybeans, or 4,000 tonnes of wheat.

These staple crops could feed 49,000, or 20,000, or 19,000 people per year, respectively.

Finally, a mature forest 10 km2 in size could sequester between 200,000 and 300,000 tonnes of carbon. This equates to a value of between $132 and $198 million if we use the social cost of carbon, which is $180 per tonne.3The social cost of carbon represents the monetary value of the long-term harm caused by climate change, including impacts on agriculture, human health, property damage from extreme weather, and changes in energy costs.

(To put this in context, Canada’s carbon price just increased to $80 per tonne. Simply doing away with the carbon price, or ‘axing the tax’, as Pierre Poilievre puts it, doesn’t change the fact that carbon emissions have a cost on society.)

Again using Barrie as an example, its GHG reductions plan notes that, in 2018, private vehicle use accounted for 580,300 tonnes of CO2e.4Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) provides an estimate of the warming effect a number of different GHG have on the atmosphere. Since GHGs like methane and nitrous oxide have a greater warming impact, they are calculated differently than CO2.

While full replacement of paved surfaces in an urban area with forest or farmland is neither feasible nor practical, it is worth thinking about the ways that we utilize the spaces we inhabit.

Isn’t it strange that we are habituated, and, importantly, habituate our children, to an environment that is inherently unsafe? Walking or cycling, or driving for that matter, requires us to be alert to the dangers posed by cars. Would a responsible parent allow their young child to walk through a parking lot alone?

Devoting so much area to private car use, given how expensive it is, both for the individual and for the planet, not to mention the fact they sit unused for the vast majority of time, should give us pause for thought.

Imagining Different Futures

Freeing ourselves from car dependence doesn’t necessarily mean that we have to go without the option of driving, anytime or, mostly, anywhere.

Rather than owning a car, we could reorient towards publicly owned car share operations. While we are used to thinking about cars as different from public transportation, such as buses or trains, they are essentially the same thing, a means to get from point A to B.

Lots where cars could be accessed would be located in each neighbourhood, within easy walking distance for residents. Instead of the two-lane feeder roads that serve the majority of our residential communities, we could have single-lane access roads for service vehicles, such as garbage, fire, or delivery vehicles.

The space freed up by removing the now unnecessary lane could be used instead for new residential buildings, for gardens, or for playing areas. Now that people no longer need a garage dedicated to their vehicles they could be converted into additional dwelling units, suitable for rentals with which extra income could be earned, or as apartments for grandparents.

The money freed up in this way could, in part and together with the revenue generated by the car share program, be plowed back into public transit, creating a truly safe and efficient system, easing congestion and serving as the backbone of the local economy.

While this might sound a bit like a flight of fancy, is it really such a stretch to imagine given the current reality requires owning an incredibly complicated piece of machinery worth a year’s salary in order to be able to get to a store to buy food to eat?

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Issue Brief’s are first published in our monthly newsletters.

Subscribe to get these in your inbox first!