Should Canada revisit the Energy East pipeline proposal to transport Alberta oil to Atlantic tidewater?

This question has reemerged from the dustbin to which it was consigned, due in large part to the unpredictability of the current U.S. administration.

The Pipeline Problem

The Energy East pipeline was first announced in 2013, and intended to transport crude oil from Western Canada to Saint John, New Brunswick.

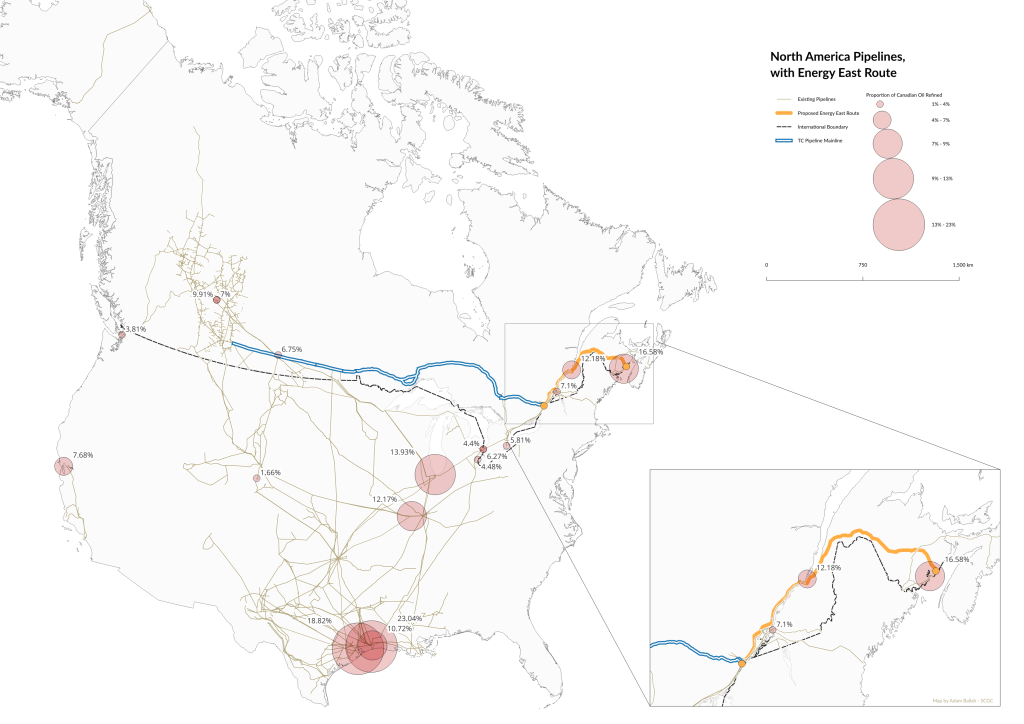

The route of the proposed Energy East Pipeline.

Initially proposed as re-purposing 3,000km of natural gas pipeline for oil, with an additional 1,600km of new pipeline construction, a new Energy East pipeline would likely have to be constructed for the full 4,600km length, due to current capacity commitment for natural gas.

(Click image for a higher resolution version.)

The pipeline was intended to carry up to 1.1 million barrels of crude per day, with an initial construction cost of $12 billion CAD, revised upward to $15.7 billion CAD in 2015.

Today, however, the cost is likely to be far more.

When the Energy East Pipeline was first proposed, it was based on the assumption that a 3,000km long stretch of TransCanada’s Mainline natural gas pipeline, shown in blue on the map above, would be converted to carry oil. An additional 1,600km of pipeline would be built to reach eastern tidewater.

Two things have happened since the initial project was shelved that significantly impact a renewed project along this route:

- Ownership has changed. TransCanada no longer operates oil pipelines, having spun those assets off into another entity, called South Bow, last year, choosing instead to focus solely on natural gas.

- And, TransCanada’s Canadian Mainline pipeline is operating near capacity, with long-term contracts for natural gas.

This means that instead of converting 3,000kms of natural gas pipeline for crude, a new pipeline would have to be built along the full, 4,600km length of the route, likely without access to TransCanada’s previous land rights and existing corridors.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Our Issue Briefs appear first in our monthly newsletter.

If you like this content, consider signing up!

Cost Model

We can estimate a new cost by looking at pipeline construction costs from 2014, updating them to factor in inflation, and then including soft costs typically associated with these projects.

In 2014, a new pipeline was estimated to cost roughly $2.8 million per kilometre. Using the Bank of Canada’s Inflation Calculator, $2.8 million in 2014 becomes slightly more than $3.6 million today.

Applying that figure to the whole length of the project, 4,600km, starts at $16.5 billion, just for the pipeline itself.

Including soft costs, including assessments and permitting, land acquisitions, engineering and labour, etc., which typically account for about 35% of the project total, and that figure rises to a baseline of more than $25 billion.

This would make it one of the most expensive infrastructure projects in Canadian history.

Let’s look at how long it would take for such an investment to pay off, next.

Could the Energy East Turn a Profit?

In 2024, Alberta produced slightly more than 2 billion barrels of oil.

Roughly two-thirds of Canada’s oil production is considered Western Canadian Select (WCS), which tends to be heavier and more costly to refine than other types of oil, which are often referred to as light or sweet crude.

In part due to the extra cost of refining, as well as due to the lack of access to diverse markets, as well as lack of refining capacity, WCS sells at a discount of between, on average, $12 to $20 USD per barrel, relative to sweeter varieties.

Energy East, proponents argued, would have opened up access to more markets, as well as access to more refineries, cutting the discount by about half.

At peak capacity, this would result in additional annual revenue for oil producers of between $2.7 and $5.4 billion CAD.

Annual Throughput = 1,100,000 barrels/day × 365 days/year

= 401,500,000 barrels/year

Added Revenue (CAD) = 401,500,000 × 10 (narrowed discount) × 1.35 (USD to CAD exchange rate) = $5.42 billion CAD in added revenue

The cost basis for producing a barrel of oil, or the breakeven point, is roughly $40 to $70 1https://financialpost.com/commodities/energy/canadian-oilpatch-volatile-oil-prices2https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/bakx-wti-wcs-alberta-budget-oil-1.7087855, depending on whether it’s in situ, or “in place”, production, which is from reservoirs that don’t require removal of overlying rock and soil, or on the upper end, from mining and upgrading projects, which do. In situ extraction accounts for roughly 50% of current production.

As you can see on the chart below, WCS prices are currently at about $48/barrel. The last time we saw prices collapse to this level was right around the time the Energy East project was called off. This is shown on the chart by the yellow highlight.

Oil price fluctuations, correlated with exposure to global shocks, tends to mean that governments and investors that rely on higher prices also have significant risk exposure.

(Note the crashes during the pandemic in 2019 and the OPEC/Russian price war in 2020, and then the spike when Russia attacked Ukraine in 2022. Oil prices are tightly linked with geopolitics, and the downward trend on the far right reflects broad pessimism regarding near-term stability.)

Modelling three scenarios, of low, average, and high oil prices, shows a break-even point for construction costs of the Energy East pipeline, as it stands today, would take between 20 years, for the low price scenario, and 10 years, for the high price scenario.

Three prices scenarios indicate when a hypothetical Energy East pipeline, with construction starting this year, would reach the break-even point.

A cautionary note: the average scenario, which assumes a $75 USD per barrel price, is, as noted, based on the post-COVID norm. Viewing COVID as an outlier may not be appropriate in our future world. If global shocks, like COVID, are more likely in the future, then this estimate has to be seen as conservative. If we average the price of WCS since 2010 to include the COVID period, the result is $55.18 USD, much closer to the bottom end of the break-even production range producers need to remain viable.

Outlook and Constraints

Given current geopolitical tensions and the impact they have had on energy markets, Canadian oil seems like it offers a stable, somewhat responsible value proposition. However, those same geopolitical tensions have heightened demand for military spending, which, it seems likely, will lead to budget constraints in other areas. Given this, the premium charged for Canadian oil – the discount mentioned above – becomes a drag factor in competition with easier to access and refine, cheaper oil, like that produced in the Middle East.

Furthermore, there’s reason to be cautious regarding future demand.

East Coast market access, while theoretically accessing a wide range of global markets through shipping routes, is currently constrained due to instability at key choke points, including the Red Sea, as well as, potentially, the Panama Canal. This largely leaves Europe and Africa as the primary markets whose access would be significantly improved by Energy East.

Oil consumption may have peaked in Europe, as the chart below shows, while Africa produces a large amount of oil, most of which is cheaper than what Canada would provide.

To quickly address the question of refining capacity: both the East Coast and Europe have refineries that can handle WCS heavy crude.

Oil consumption in the markets most likely to be supplied by Energy East are flat to declining.

Finally, the International Energy Agency estimates that oil demand is likely to slow significantly by 2028, due to the rise of renewables and increased electrification.

Conclusion

The primary question driving the renewed debate regarding Energy East is the need for diversification. The argument here is that by being so beholden to the U.S. market, Canada both loses out on opportunities to take advantage of global oil demand, and exposes itself to pressure from the U.S. in the event of an antagonistic relationship, as we’re seeing now with the Trump administration.

This argument is an important one, considering how it could impact Canada’s economy and sovereignty. However, to maintain the rational consistency, we must open the aperture of the need for diversification argument to additional, equally important areas.

Energy sources need to be diversified. A heavy reliance on fossil fuels exposes our economy to significant risk, as we are seeing with the current downward spiral in oil prices and the heavy impact that is likely to have on the budgets of governments that rely too much on them.

When it comes to the environment, this need for diversification, in terms of our options, is increasingly urgent.

The path to maintaining the goal of keeping global warming beneath the 1.5° is narrowing. We have already seen our first year in which global temperatures exceeded, at 1.55°, this threshold. (2023 was 1.48° above that 1850-1900 pre-industrial baseline.) (Whether we’ve passed that mark is determined by the 20-year running average anomaly relative to the baseline.)

Finally, diversification and energy supply resilience can be accomplished with further rollout of renewables and increased grid interconnection. A worst-case scenario places a singular asset, like a pipeline, at extreme risk. True diversification would mean investing in distributed, renewable, and resilient energy systems — ones that can weather geopolitical storms, economic shifts, and ecological limits alike.

Given the enormous cost of a new-build pipeline, the shrinking global appetite for oil, emerging competition from cheaper producers, and the risk of future climate-driven shocks, Energy East appears more likely to become a stranded asset than a national strategy.