2,864 words, 15 minutes read time.

Risky Business

Insurance is something we all love to hate, until we need it.

The kicker with that is, if we’re lucky, we never face a situation in which we need it, and then all the money we’ve put towards it is, in effect, a sunk cost.

Insurance is a hedge against risk or uncertainty, and bundled with that is the possibility that the unknowns that shape the path we take into the future may not throw us that proverbial curveball. Whether our hedging will be useful, in other words, whether, in fact, we will be confronted with some unforeseen circumstance that causes a divergence from normality, that shakes our stability, is also uncertain.

So, paying for something that you may never actually need can be a difficult pill to swallow.

This calculation changes, though, when we’re in an environment where there’s an increased likelihood of risk. Climate change, by increasing weather instability and impacts, is increasing our exposure to risk. As costs of climate impacts mount, it is becoming increasingly difficult for insurers to make a profit, which means they are both developing new strategies in an effort to make their product profitable, and, in some significant cases, withdrawing their product from certain markets entirely.

Insurers have identified two general categories of climate risk – physical, which involves acute and chronic changes, like a hurricane or sea level rise; and transition, which involves policy changes, legal challenges, technological shifts, and market dynamics.

Early Adopters

Around the time Exxon was suppressing internal research on climate change in the 1980s, the insurance industry was starting to recognize changes in severe weather patterns, though causal linkages to climate change were not yet being made.

Beginning in the early 90s, the industry realized that their traditional models of risk evaluation were underestimating the impacts of climate change, and work started on updating them to more accurately reflect potential risk losses related to severe weather events.

In the 2000s, the industry started to engage with policy and regulatory frameworks, pushing for more sustainable development practices that addressed risk reduction concerns, as well as integrating similar policies within their own operations and applying them to their underwriting models.

In the 2010s, insurance products started to be tailored to the now broadly accepted reality of climate change. Policies were narrowed to address more specific events, with more clearly defined parameters for when and how claims would be paid out.

Today, insurers continue to integrate climate risks into their business models, have expanded their engagement with policymakers in pursuing climate resilience and environmental stewardship, and are developing methods, like cat bonds, for insulating funds from potential impacts associated with natural catastrophes.

Impacts

When Hurricane Andrew hit Florida in 1992, it missed downtown Miami by 50 miles. Winds as high as 174 miles per hour destroyed more than 63,500 homes, damaged more than 124,000 others, and caused damages equivalent to $26.5 billion USD. 65 people were killed in the storm.

Since Andrew, there have been 14 hurricanes that have exceeded $5 billion in damages, including Katrina ($125 billion), Maria ($91.4 billion), and Ian ($113 billion). Prior to Andrew, Hurricane Hugo, in 1989, cost $10 billion, and Gilbert, in 1988, cost just under $3 billion. Damages from hurricanes before those didn’t exceed $1.7 billion.

Wildfires, too, are wreaking havoc.

Dramatic temperature swings, like what was caused by the Arctic air mass that swung down to Texas a few years ago, can wreak havoc on infrastructure, as it did their power grid.

These are all examples of a climate that is veering out of control. Research shows that storms that occurred roughly every 100-years, so-called 100-year storms, are likely to occur more frequently, every 3 to 20 years.

This increase in frequency and severity has come at a cost for insurers, and, in some of the more risk-prone areas like Florida and California, larger companies, like State Farm, have decided that it’s simply too costly to continue to offer policies, and have withdrawn from the market.

Risk Begets Risk

In response to insurers withdrawing, governments have established backstop, or last resort, coverage. Governments have also lowered regulations that require a degree of certainty in the insurer’s ability to cover damages. This can be seen in another outcome of traditional insurers withdrawing from markets due to escalating climate-related risks, which is the emergence of lower-quality insurers. These tend to be newer companies, which are less diversified and under-capitalized.

Similarly, the financial stability of these new companies, assessed by rating agencies, have increasingly been done by new agencies, meeting regulatory criteria that are less strict. Concerns have been raised regarding the quality of the ratings these newer agencies are providing, as the solvency, in the event of a larger-scale catastrophe, of some of the smaller insurers they’ve approved is questionable.

One of the key differences between Canada and the U.S. in insurance, is how mortgages are securitized. Financial stability ratings play a similar role in both countries, but in Canada the ratings agencies remain for the most part large, well-established players.

In the U.S., the role of securitization, which is essentially an assurance that the underlying asset will be valued if it’s called upon, is done far more by government supported enterprises (GSE’s), like Fannie Mae and Freddy Mac. Banks and other lenders respond to risk by offloading mortgages to these GSE’s. When insurers go insolvent, the financial stress that households experience after a natural disaster is exacerbated, leading to increased mortgage delinquencies.

As more low-quality insurers assume responsibility for policies, the risk that a default is passed on to those that securitize the assets grows.

This risk is more acute in the U.S. than in Canada due to the role of government in providing a backstop, in the form of securitization by GSE’s, and in the presence of less stable insurers in the marketplace. Mortgage lenders in Canada require adequate insurance coverage for properties, and, unlike the U.S., where GSE’s buy and securitize mortgages, Canada’s mortgage system relies more on direct bank lending, with some securitization handled by CMHC.

Counterintuitively, for those familiar with the respective roles of government in public life in Canada and the U.S., its presence here contributes to risk by enabling risky behaviour. In effect, due to lax regulations and ratings that allow financially fragile insurers to dominate high-risk markets, a large portion of risk associated with climate change has been transferred from private actors to the public sector.

Innovation

Insurers have also been changing their product to address the increase in uncertainty.

Parametric modelling implements triggers based on an event reaching pre-established parameters, like the wind of a hurricane reaching a certain speed, or the magnitude of an earthquake. Parametric insurance focuses more on specific, measurable events.

Index-based insurance is similar, in that it uses pre-defined parameters, but are more related to rainfall or temperature, and focuses more on community-level environmental factors. An index-based policy might pay out if rainfall is below a certain amount, for example, resulting in drought.

The benefit of this approach is that payouts to those affected can be made faster, since the easier identification of the threshold, like wind speed, removes much of the assessment process formerly used to determine whether and how a policyholder was impacted.

There may also be benefits to these approaches of encouraging adaptation and building resilience, as the clearly defined thresholds effectively establish certain parameters or tolerances, like the ability of a construction material to withstand a specified wind speed or efforts to mitigate the impact of drought on a crop. By establishing parameters, these models can further disperse risk throughout the economy, placing greater onus on regulators, manufacturers, builders and architects, and others to meet established parameters.

Deterring Risk

By assuming the costs associated with risk, however, governments are subsidising risky behaviour by making it more affordable.

While insurance is a crucial mechanism to help people hit hard by catastrophes get back on their feet, if done wrong, it can also increase the chances that people will be affected in some form by those same catastrophes. By insulating people from the costs associated with their actions, the political imperative to act on factors shaping that behaviour, and those risk factors, is dulled.

It may be fashionable to write the insurance industry off as simply another business interested only in making money off of people, but the product it offers, the hedge against uncertainty, is an important component of social and economic resilience, and, perhaps counterintuitively, when it comes to insurance, there’s a case to be made that private provision, as opposed to public provision by government, can play an important role in navigating an increasingly uncertain climate.

More accurately pricing risk, such as the likelihood of costs associated with purchasing a home located on a floodplain, can act as a deterrent to risky behaviour. This can support policies and shape behaviour that enhance overall resilience to climate impacts. Put simply, if it’s more expensive to buy a house located on a flood plain, it’s less likely that people will do that.

Dispersing Costs to Increase Resilience

There are varying degrees of ability to respond to costs associated with climate risk, though. In some cases, that ability comes through the form of being able to pay higher premiums, or to move to live where there’s less risk.

These are scenarios where the ability of an individual to make a choice, such as whether to pay more or to live elsewhere, is a key factor. In many cases, however, the ability of an individual to choose is far less.

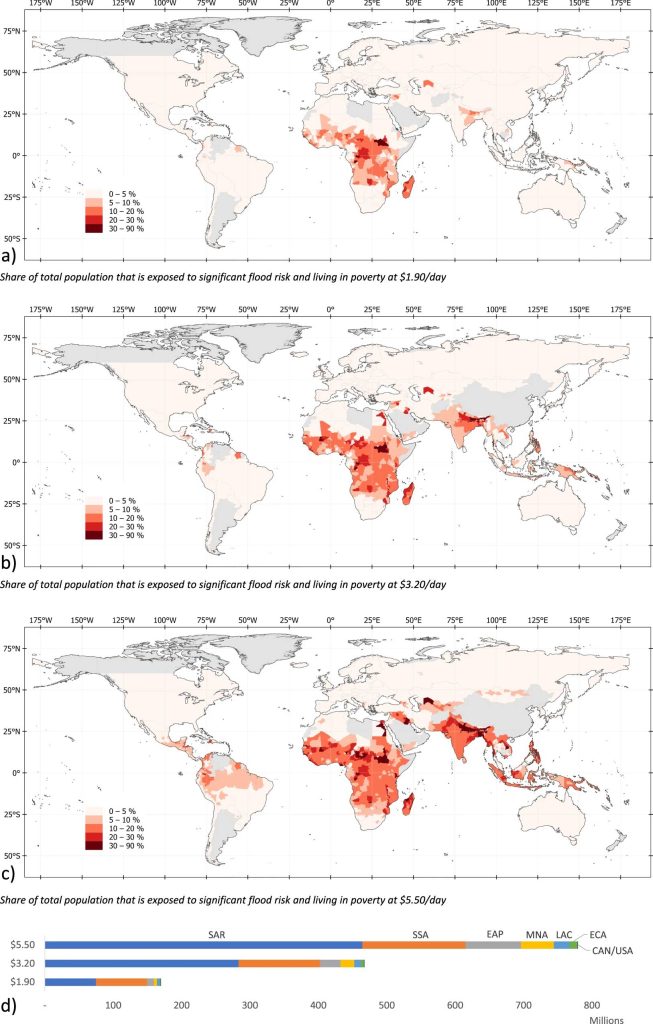

When someone is born in a region where climate risks are especially acute, or where economic options that might enable one to move to a less risk-prone area, or pay those higher premiums, are limited, there is little choice but to confront the high costs associated with living in the line of fire.

Many Caribbean countries, for example, are especially vulnerable to climate change, and their populations are, by and large, less able to pay for higher insurance premiums or for measures, like flood-proofing homes, that enable them to better withstand catastrophes.

In 2007, the Caribbean Regional Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF), became the first multi-country risk pool. Developed with the understanding that greater resilience could be achieved by combining assets to address the costs of catastrophes.

By spreading costs associated with risk across a much broader population, and across a much larger area, the probability of an all-encompassing impact is reduced, while the basket of resources that can be drawn upon in the event of a catastrophe are both diversified and increased.

In areas, like Caribbean nations, where exposure to risk is high and options to ameliorate it are constrained, spreading risk and pooling resources can greatly improve resilience to catastrophic impacts, and the moral hazard of enabling individuals to live in high risk areas is negated. This approach has since been adopted by other regions with high risk exposure and constrained capacity, including the African Union and the Pacific Islands Forum.

Another way that risk is dispersed is through the role of reinsurers. Insurers often get portions of their portfolios reinsured by other companies. This can increase the stability of insurance, as companies purchasing insurance portfolios from other insurers have a vested interest in the soundness of the product. Furthermore, reinsurance help stabilize primary insurers from risks of insolvency in the event of catastrophe by acting as a portion of the payout has been offset in the reinsured package.

As uncertainty has grown, however, both in weather and the industry, reinsurance rates have increased. In Canada, in 2023, this has been by 25-70%. This cost premium highlights the reliance of insurers on the reinsurance market to manage risk, and creates a challenge for smaller insurers in terms of whether they are able to justify the cost, or whether they simply accept that they may not be able to remain solvent in the event of a catastrophe, which, in turn, may impact market stability.

Combining the Public and Private Approaches

When it comes to addressing risk exposure, well-regulated private actors, like large insurance companies, tend to be far more accurate and risk-averse than those that are poorly regulated, like the smaller, new insurance companies, and government.

Governments can assess risk with a high degree of accuracy – in fact, much of the data used by insurance companies comes from government agencies. It can be more difficult for government to move on an issue, though, if the political support isn’t there.

Governments can offer coverage that is more accessible, so that those unable to afford the higher premiums of private insurance are able to gain some coverage. Providing external support in the form of subsidies, reinsurance, and technical support, can help address issues of fairness and equity that would otherwise either be difficult to overcome for a business that needs to remain solvent, or for an industry that needs stability, but which is, itself, increasingly exposed to uncertainty regulatory oversight and questionable practices.

Private insurance, on the other hand, has started to use modelling that provides more granularity in determining risk exposure, taking into account variables like topography, as well as vegetation type and density. This helped to more accurately identify where risk was greater, and to price coverage in those areas accordingly. Areas where the topography is more exposed to flooding, or where the vegetation is likely to catch fire, to continue with the two examples, are priced for their higher risk profile, while nearby areas, perhaps just up the hill, rather that in the valley near the river, are priced for their lower risk profile.

Public Education and Awareness

Even as our understanding of climate impacts improves, far too many remain uninformed and misinformed. This lack of good information impedes our ability to effectively respond to changing circumstances, resulting in higher costs, both to our economy, and on the lives of those directly affected.

Governments can counter misinformation, and the knock-on impacts it has upon risk exposure, by engaging with communities proactively to identify threats and vulnerabilities, and by addressing those vulnerabilities so that they are shored up to better withstand potential impact.

Further, engaging with the insurance industry to accurately assess risk and vulnerability, and to communicate clearly the advantages that investing in resilience has for communities, can help make the case that up-front costs will pay off in the long run.

And, incorporating accrual accounting into government planning, where the depreciation of public assets, like roads, is factored into the balance sheet, can provide a better picture of potential liabilities. Under an accruals-based system, such as that used in New Zealand, the costs associated with the deterioration of an asset, like a road, are included, while a cash-based system simply counts the costs of repair or replacement when it occurs.

This means both that investment in maintenance is often deferred, placing it onto future generations, and that governments can be somewhat careless with planning where and how infrastructure is built in the first place.

Incorporating the full cost into the budgeting process can ensure both that investments are done in a less risk-exposed way, and that additional financial burdens are not displaced into the future, where it seems increasingly likely there will be less capacity to address them.

Conclusion

This brief underscores the escalating climate-related challenges facing the insurance industry, as well as the need for balanced risk management and regulatory oversight. While climate risks are pushing insurers to withdraw from high-risk areas and adopt new products, like parametric and index-based insurance, these adaptations are not always sufficient for vulnerable populations or regions.

One of the core issues is the transfer of risk from private insurers to the broader public and financial sectors due to lax regulatory standards, especially in high-risk areas where financially fragile insurers tend to dominate. This situation is further complicated by the interdependency of insurance and mortgage markets, particularly in the U.S., where government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) increase the potential for systemic risk.

A proposed hybrid model combines the strengths of private insurance with public sector support, including reinsurance for catastrophic events and financial assistance for low-income households. This approach could stabilize the insurance market, make coverage more affordable, and encourage resilience by sharing risk more widely.

In Ontario and Canada, more established regulatory structures offer some insulation from these risks, though challenges persist. Climate impacts continue to drive up home insurance costs, which rose 7.8% year-over-year—well above the rate of general inflation. For lower-income households, these cost increases pose affordability challenges, underscoring the urgency for policies that balance cost-sharing, affordability, and resilience in the face of growing climate uncertainty.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Issue Brief’s are first published in our monthly newsletters.

Subscribe to get these in your inbox first!