“The longest freshwater beach in the world is more than just a place to swim—it’s a sanctuary for species at risk and a space for Ontarians to connect with the natural world.”

Ontario Parks

“…portaging is like hitting yourself on the head with a hammer: it feels so good when you stop.”

Bill Mason, Canoeist and Educator

Background

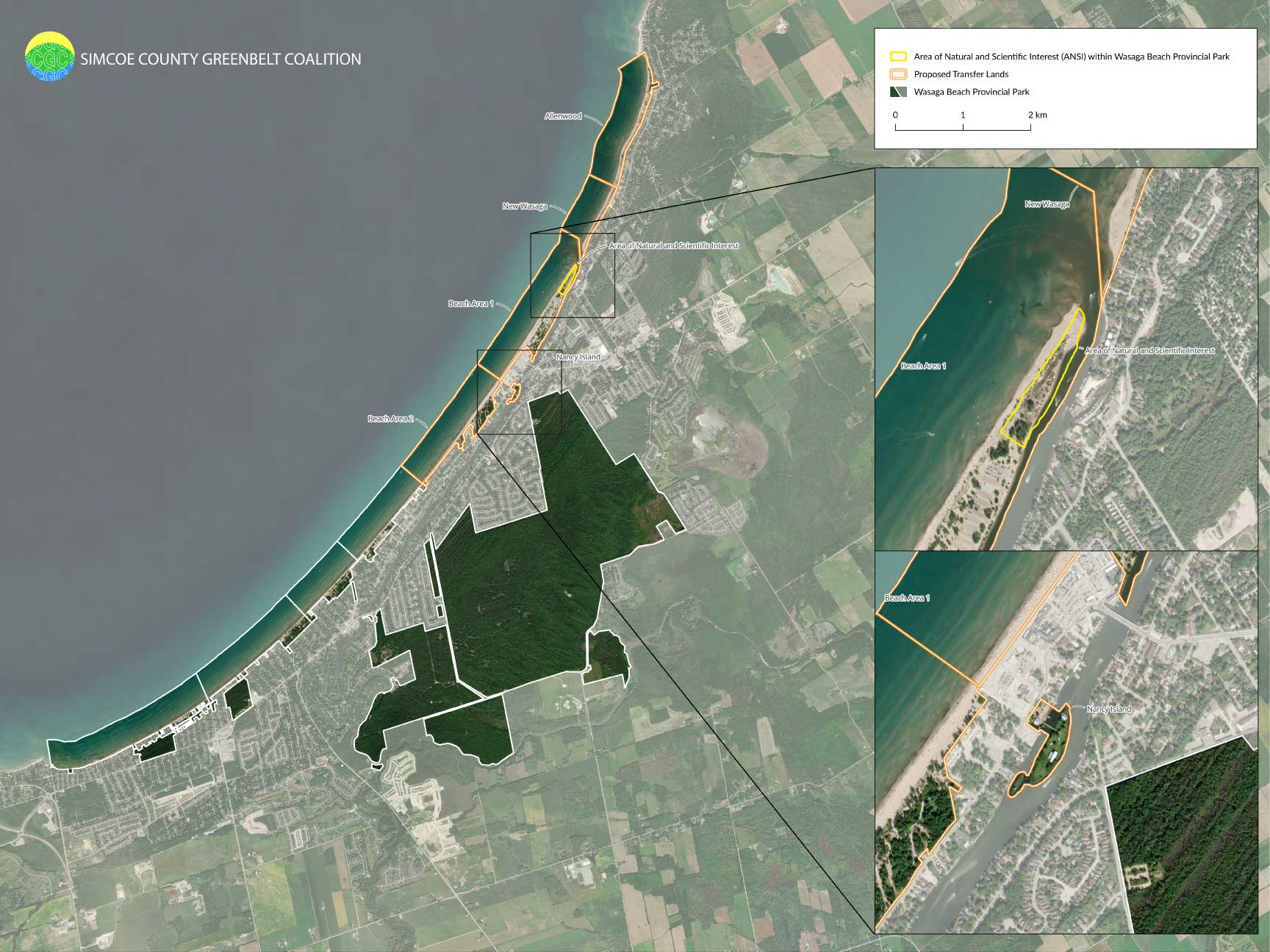

In June 2025, the Ontario government announced a proposal to transfer several areas within Wasaga Beach Provincial Park—including Beach Areas 1, 2, New Wasaga, and Allenwood Beach—to the Town of Wasaga Beach. Nancy Island would also be transferred, but to Huronia Historical Parks, which administers Discovery Harbour and Sainte-Marie among the Hurons.

This proposal follows a unanimous motion passed by Wasaga Beach council nearly a year earlier, requesting that “Nancy Island, Beach Areas 1 and 2, a portion of Beach Area 4, and all remaining non-Beach Area and non-environmentally sensitive parcels of land be transferred out of the MECP [Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks] portfolio.” This motion came shortly after a meeting between the council, senior staff, and Premier Doug Ford, and aligns with recommendations from the town’s Economic Development and Tourism Advisory Committee.

It is important to distinguish between clearly defined areas (such as Beach Areas 1 and 2) and the additional request for non-environmentally sensitive parcels. This should not be interpreted as a request for only non-sensitive lands; rather, it includes both the identified areas and any other parcels deemed not environmentally sensitive.

The province has framed the proposed transfers as supporting the goals of Destination Wasaga, an initiative launched in spring 2025 that aims to turn Wasaga Beach into a year-round, world-class tourism destination.

While the town’s five-point plan highlights the need to balance economic, tourism, and environmental interests, and the province has stated that the beach “will remain public,” the proposal raises questions about how that balance will be achieved, and how “public” will be defined in practice.

Crucially, the province is also proposing legislative changes to facilitate the transfers, circumventing existing regulatory processes. Although the changes are presented as specific to Wasaga Beach, they would apply across Ontario, raising concerns about broader impacts on the provincial park system.

Lands the province is proposing to remove from Wasaga Beach Provincial Park, and to hand over to the town of Wasaga Beach and Huronia Historical Parks, are outlined in orange.

Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI) land is outlined in yellow.

The Nottawasaga watershed is outlined, and the significant terrain features surrounding it identified.

Click on the map for a higher resolution version.

History

Wasaga Beach is home to the world’s longest freshwater beach: 14 kilometres of near-continuous sand stretching into Georgian Bay. The gently sloping lake bed allows visitors to walk far into the bay before the water deepens, and the warm, shallow waters have made Wasaga a popular vacation destination for more than a century.

Natural History

The area’s fine sand is a result of glacial retreat. When the massive Laurentide Ice Sheet melted, it formed Lake Algonquin—larger than present-day Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron combined. As water from Lake Algonquin drained through the St. Clair River, fine sediments were deposited along what are now the Nottawasaga watershed’s channels and basins. (See our previous Issue Brief on the Nottawasaga Watershed for more.)

Tourist Economy

The name “Wasaga” comes from the Anishinaabemowin word waasaagamaa, meaning “clear or shining waters.” The beach became a magnet for summer tourists, with attractions like the Dardanella Dance Hall, a boardwalk, and beachfront hotels. During World War II, Camp Borden soldiers also frequented the town. By the 1980s and 1990s, Wasaga Beach saw over a million visitors annually, with up to 100,000 on peak summer weekends.

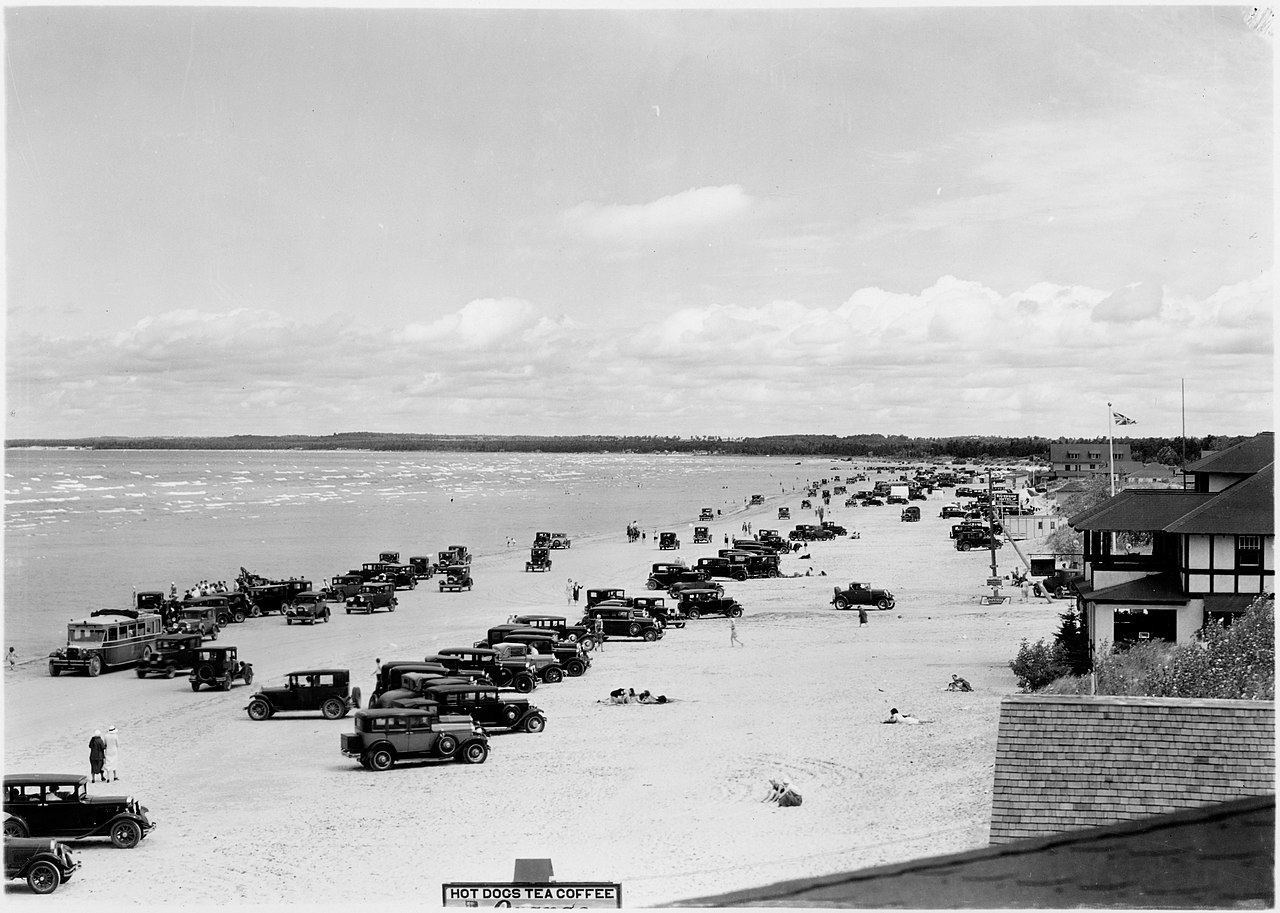

Photo of Wasaga Beach from around 1925.

The cars parked along the beach reflect how the rise of the automobile was reshaping the way Ontarians vacationed and explored their province—where travel had once depended on trains or horse-drawn wagons. They also serve as a reminder of how our understanding has since evolved about the environmental impacts of such activities on beaches and coastal ecosystems.

In 2007, a massive fire destroyed roughly 90% of the buildings on the main strip at Beach Area 1. Many properties were underinsured or absentee-owned, and redevelopment has largely stalled.

Visitation declined significantly, with approximately 100,000 fewer visitors annually between 2002 and 2012. A proposed year-round resort-style development collapsed in 2010 when developers faced bankruptcy and fraud charges.

Notably, there is no evidence that environmental regulations were a barrier to redevelopment.

Current Context

In 2015, the town purchased about 70% of the main strip for $13.8 million—nearly 70% of the property tax revenue collected that year—using loans from a bank and the province.

While tourism has rebounded post-COVID, and Wasaga Beach is currently the most visited provincial park, the main strip remains fragmented and underutilized. Commercial activity is focused on one-stop, day-trip shoppers rather than the higher-value, overnight tourism market.

Town Planning

In 2017, the town adopted the Downtown Development Master Plan (DDMP), a 20-year strategy involving $625 million in capital investment to revitalize the area.

In spring 2025, the province pledged $38 million under Destination Wasaga, including:

$25M for Nancy Island redevelopment;

$11M for rebuilding the main drag;

$2M for tourism planning.

These align with the DDMP’s goals.

Local Control

The town has expressed frustration with MECP’s handling of park facilities. Issues like unsanitary or closed privies at Allenwood Beach have been a particular sore point. The town now contracts for cleaning services, and as of writing, the facilities are operational.

The Allenwood Beach area is a unique case—it is owned by the town but still lies within the provincial park boundary, reinforcing the town’s interest in gaining more control over key areas.

Provincial Deregulatory Agenda

The proposal comes amid broader provincial efforts to centralize decision-making, reduce regulatory oversight, and expand private sector involvement. These moves are justified as responses to the housing crisis and, more recently, to economic threats like U.S. tariffs.

Legislation such as Bill 5 has enabled the province to override local planning decisions, reduce environmental safeguards, and limit public consultation. This centralization has narrowed the scope of decisions to reflect the priorities of the Premier’s Office more than those of the public.

Piping Plover Habitat

Compounding the complexity of any redevelopment plans is the presence of the Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus), a small, endangered shorebird that has returned in recent years to nest on Wasaga Beach’s sandy shores. The species is federally and provincially protected under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) and Ontario’s Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Wasaga Beach is one of the few nesting sites in Ontario for the Piping Plover, and its successful return has been considered a significant environmental achievement. Active conservation efforts—including fencing off nesting areas, monitoring hatchlings, and public education campaigns—have been instrumental in supporting their fragile population.

The presence of the plover imposes seasonal restrictions on activities in nesting areas, including limitations on recreational use, shoreline grooming, and nearby construction. As such, any redevelopment in or near these zones must take these constraints into account and may require additional environmental assessments and regulatory approvals.

The potential transfer of lands currently under the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act raises concerns about whether these protections will remain as robust under municipal oversight. While the town may choose to maintain such protections, it is not legislatively required to do so, and shifting governance away from the province could expose this critical habitat to greater risk—particularly if future councils face competing development pressures.

Proposed Changes

The ERO posting presents the Wasaga Beach transfers as justification for amending the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act (PPCRA) and the Historical Parks Act. However, the changes would apply to all provincial parks.

“We are seeking input on proposed amendments to the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006, (PPCRA) and changes to the Historical Parks Act (HPA) to restore an important heritage site to boost tourism and drive economic growth in Wasaga Beach, while continuing to support the area’s natural and cultural heritage.”

— Environmental Registry of Ontario (ERO) Posting

Two key issues are therefore at play:

The transfer of specific lands to the municipality, with changes in regulatory oversight.

The amendment of provincial legislation, potentially affecting parks province-wide.

Land Transfer Details

The mayor has stated that the province is considering the transfer of “less than 60 hectares—just 3% of the park’s 1,844 hectares—back to the municipality.” That, “roughly half of the proposed land includes beach and environmentally sensitive dunes – areas that will be preserved.” Leaving, “about 30 hectares, mostly paved parking lots, that could be reimagined through a thoughtful, community-led Waterfront Master Plan.”

However, when water lots (lake and riverbed portions) are included, the park is being reduced by nearly a third. Only a tenth of that reduction will transfer to the town, but the full one-third will lose protection under the PPCRA.

Under the PPCRA, ecological integrity is the legislative priority. Once removed from that framework, land is subject to municipal planning decisions. While municipalities canmaintain environmental protections, they are not required to do so by law.

Section 9(4) of the PPCRA

Currently, under Section 9(4) of the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act (PPCRA), any reduction in park area amounting to 50 hectares or more—or 1% of the total park area—must follow a legislative process:

The Minister must submit a report to the Legislature

The proposed boundary changes must be tabled

The Legislature must vote on whether to approve them

This process reflects the principle that provincial parks are a public trust shared by all Ontarians, not solely under the purview of local or provincial executives.

In past cases where reductions did not exceed these thresholds, the government adhered to the process. For example:

In 2011, 1 hectare was removed from West English River Provincial Park for a sewage treatment plant.

A proposal to remove 12.5 hectares from Grundy Lake for Highway 69 expansion is currently open for public comment.

However, in the current case, rather than following this process, the government is proposing to amend the PPCRA itself—a far more sweeping measure with province-wide implications.

Yet it remains unclear why this is necessary.

According to the mayor of Wasaga Beach, only 30 hectares—largely consisting of paved parking lots—are expected to be “reimagined.” The remainder of the proposed lands, including environmentally sensitive dunes and beachfront areas, are to be preserved.

If this is truly the case, then the province could simply limit the transfer to the 30 hectares in question, remaining well below both the 50-hectare and 1% triggers established in Section 9(4).

This would achieve the town’s development goals while respecting the legislative framework that protects Ontario’s parks.

Instead, the province is proposing to remove nearly a third of Wasaga Beach Provincial Park—only a small fraction of which will be transferred to the town. This calls into question the real motivation behind the move.

Why alter foundational environmental legislation across the province if the stated goals can be achieved within the current legal framework?

No justification for bypassing the established process has been provided.

Concerns and Possible Outcomes

The town’s desire for local control over land central to its economy is understandable. But the proposed changes carry significant risks for environmental protection and public access.

Too often, economic growth becomes the overriding priority. Promises of new revenue streams, whether from user fees or development, can outweigh protections for species like the Piping Plover or dune ecosystems.

Political incentives skew toward short-term achievements. A budget surplus or new development is easier to campaign on than the preservation of a wetland or endangered species habitat.

While the mayor and province assert that protections and access will be preserved, no mayor or cabinet can bind future governments. The mayor’s claim that “municipal stewardship allows for more community-led protection” cannot be guaranteed in perpetuity.

That said, a path forward may exist. The town’s Five Point Plan suggests the creation of a commission similar to those under the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport (e.g., Niagara Parks Commission, St. Lawrence Parks Commission, Huronia Historical Parks). These semi-autonomous, arms-length bodies can balance development with conservation—if properly structured.

A Wasaga commission could provide a model for shared governance, with community input and binding commitments around public access and ecological integrity.

But crucially:

This could be done without amending the PPCRA.

So why change the law?

We are left to speculate. Based on this government’s record—its weakening of Conservation Authorities, preference for backdoor tools like Ministerial Zoning Orders, and limited transparency—concerns are well-founded.

Without strong public scrutiny, the risk is not just to Wasaga Beach, but to Ontario’s entire system of parks and protected areas.

Final Thoughts

Wasaga Beach may be the test case. But the stakes are much larger.

The PPCRA was designed to protect Ontario’s parks for the long term—beyond the whims of any one government. If that framework is weakened, it will be much harder to restore.

For the sake of future generations, the province must pause and justify its actions. The existing process can accommodate this transfer. Changing the law to avoid public oversight would be a dangerous precedent.

So, what can you do?

We hoped to finish this brief before the Environmental Registry of Ontario (ERO) posting closed. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to—and, realistically, this government has shown little responsiveness to public input submitted through the ERO process.

That’s why we believe a more direct approach might be more effective.

We’ve created a mailto link that opens a new message in your default email app. The “To” field is pre-populated with the email addresses of Wasaga Beach Town Council. The “Cc” field includes the Premier’s Office, relevant Ministers and MPPs, and the local MPP.

We’ve left the subject line and message body blank.

Why?

Because you’ve read this far. You know the issue. And your own words will carry more weight than a copied message. Decision-makers are far more likely to engage with something that feels personal and informed than with a mass message.

Draw from the information above if it helps—but speak from your own perspective. Be clear about your connection to Wasaga Beach, to Ontario’s parks, and to the values that matter to you.

Let them know what kind of solution you’d support—whether it’s a community-led parks commission, a limited transfer within existing legislation, simply preserving the integrity of the PPCRA, or something else we haven’t mentioned.

This is a moment when your voice really can matter.

Want to share your opinion? Take our poll on this issue, here.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

A monthly newsletter with information on what’s happening in Simcoe County and beyond. This is the place for first-look access to community polls and Issue Briefs.