“The health of our waters is the principal measure of how we live on the land.”

Luna Leopold, son of Aldo Leopold, “A View of the River” (1994)

“A river cuts through rock, not because of its power, but because of its persistence.”

James N. Watkins

The Nottawasaga watershed covers approximately 3,700 km² in central Ontario, stretching from the Niagara Escarpment and Horseshoe Moraine in the west, to the Oak Ridges and Oro moraines in the south and east. Shaped like a shallow bowl, it collects water into one of the region’s most ecologically important wetland systems, the Minesing Wetlands, before draining into Georgian Bay.

While it may appear healthy on the surface, the Nottawasaga watershed has a history of ecological collapse, and is among the most fragile in the region.

Unlike neighbouring watersheds that benefit from deep aquifers, stable lake systems, or controlled flow regulation, the Nottawasaga is dominated by sandy soils, high runoff, and largely unregulated surface flows. Its ecological balance is maintained not through engineering, but through the buffering function of forests, wetlands, and groundwater systems.

This brief outlines the geographic, ecological, and historical factors that make the Nottawasaga watershed uniquely sensitive to disturbance, and examines how recent policy changes, particularly the weakening of Conservation Authorities and land-use planning protections, are undermining the region’s long-term viability.

Naadwezaagiiye

The Nottawasaga derives its name from the Anishinaabe term, “Naadwezaagiiye”, which means “where the enemy comes out of” (put politely). As Jeff Monague explains in this video he did with us several years ago, the Nottawasaga was part of a key transportation and trade route, and lookouts were posted on the heights of the Blue Mountains to spot when canoes appeared at the mouth of the river where Wasaga Beach is now.

The route wound its way from Lake Simcoe, known by the Anishinaabe as Zhoonyaa Gaaming (Place of the Shining Water), following, roughly, the path of the more recently established 9 Mile Portage, over the hills near what’s now known as Snow Valley, connecting with Willow Creek, then the Nottawasaga River and up to Georgian Bay, or Gchi-wiikwedong (at the great bay).

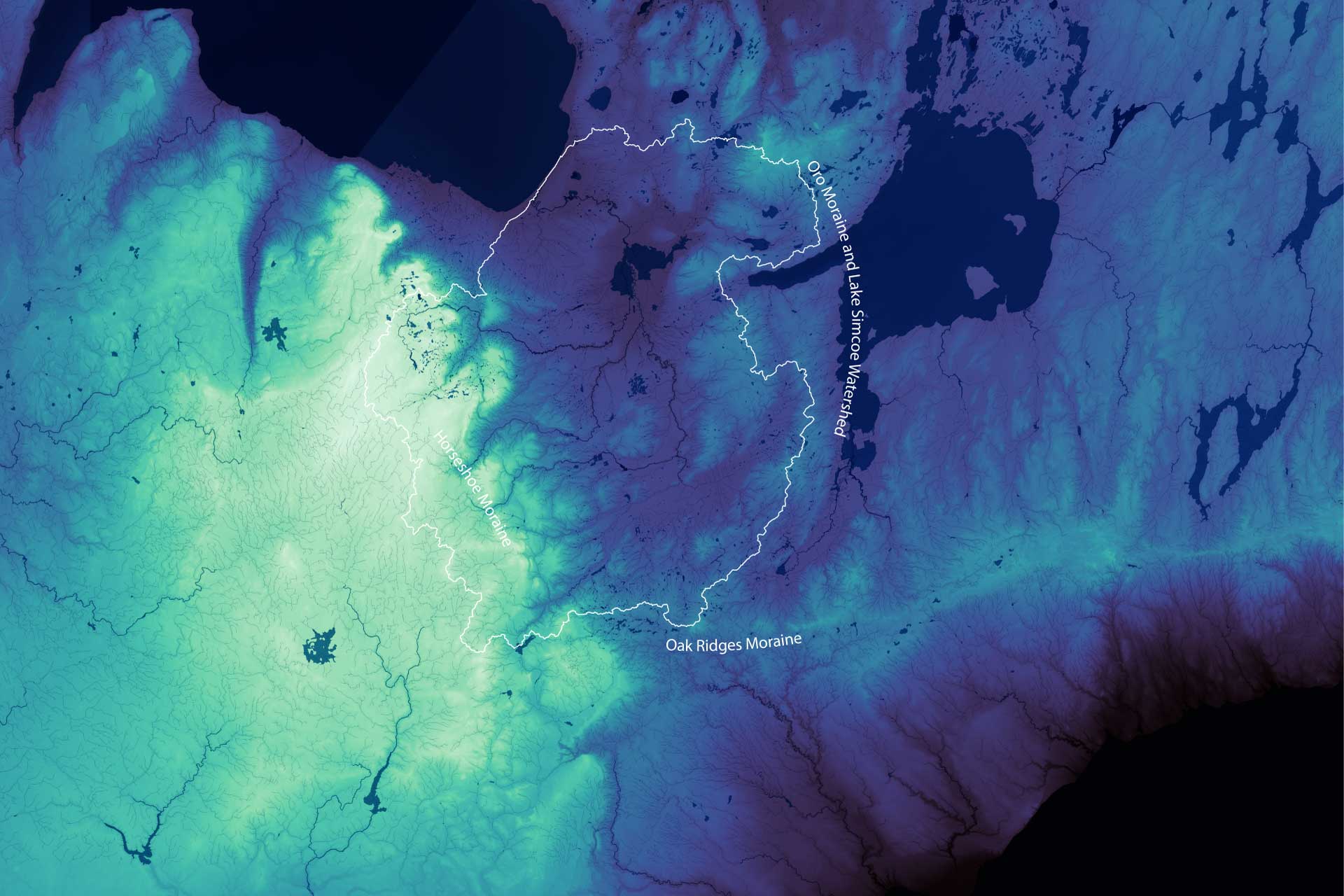

This map shows elevation in the central Ontario region, with lighter colours representing higher elevations and darker colours lower elevations.

The Nottawasaga watershed is outlined, and the significant terrain features surrounding it identified.

A similar map with elevation rendered in blue relief is available for purchase on our e-store.

Click on the map for a higher resolution version.

The Nottawasaga is mid-sized in terms of its discharge, with an average drainage of approximately 25 cubic metres per second (m3/s), or around 790 million m3 annually. This is more than many of the large rivers that flow south from the Oak Ridges Moraine and empty into Lake Ontario, including the Don and Credit Rivers, but less than the Trent (131 m3/s), and the Humber (36 m3/s), or the Severn, which discharges between 45 and 55 m3/s, or roughly 2.7 billion m3 per year.

Among rivers that empty into Georgian Bay, however, the Nottawasaga is among the smallest of the large rivers in terms of discharge, with the Spanish River, which exits to the west of Killarney, discharging between 200 and 300 m3/s, the French River (200–240 m3/s), down to the Key River, just ahead of the Nottawasaga, at 30–50 m3/s.

Geography Is Character

Key differences in geography, as well as land use, influence the discharge rates of respective river systems.

The Nottawasaga’s hydrology is dominated by a river and stream system, with significant wetland features. The rivers and streams are generally fed by runoff from permeably lands, like forests and farmland, as well as wetland storage and groundwater, and are largely unregulated by dams or other infrastructure.

As such, the flow, at least upstream of the Minesing Wetlands, can vary significantly depending on weather patterns. Those of us who live in the area will likely have seen at one time or another the flooded banks of the Nottawasaga River during the spring as the snow melts. The centrally located Minesing Wetlands act as a sponge of sorts, buffering and absorbing high volume flows from upstream, creating a more gradual and even release of water downstream.

Those of us familiar with the Nottawasaga River will also know that its waters tend to be brown, or turbid. The high turbidity has a lot to do with this runoff from permeable land, as well as its relatively slow, meandering course, which, contrary to fast running waters, allows for more sediment to build up and remain suspended in the water.

The nearby Lake Simcoe watershed, on the other hand, is dominated by that large body of water, into which numerous rivers and streams feed. The larger body of water also allows sediment to settle, resulting in clearer waters downstream as it flows through Lake Couchiching, into the Severn, and out to Georgian Bay.

The Trent has a larger drainage area, over 12,000 km2, and also relies to a significant extent on lakes, as well as coldwater input from the Canadian Shield. Water levels in the Trent watershed are also actively managed, which helps to sustain year-round baseflow.

The Humber watershed is a much smaller area, only 900 km2, but it descends rapidly from the Oak Ridges Moraine to Lake Ontario, which, when combined with far more urbanized area, with runoff from impervious surfaces like roads and roofs, along with its tributaries, valley networks, and groundwater recharge, creates higher flows than the Nottawasaga’s more rural, wetland buffered flows.

Geography is Also Economy

14,500 years ago, the Nottawasaga watershed, and much of Canada, was covered by the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Global temperatures had been slowly increasing from their Ice Age peak (or depth as it were) several thousand years earlier, with the Northern Hemisphere seeing an increase of roughly 6-8°C. This led to a process of geological transformation, the scale and force of which is difficult to imagine.

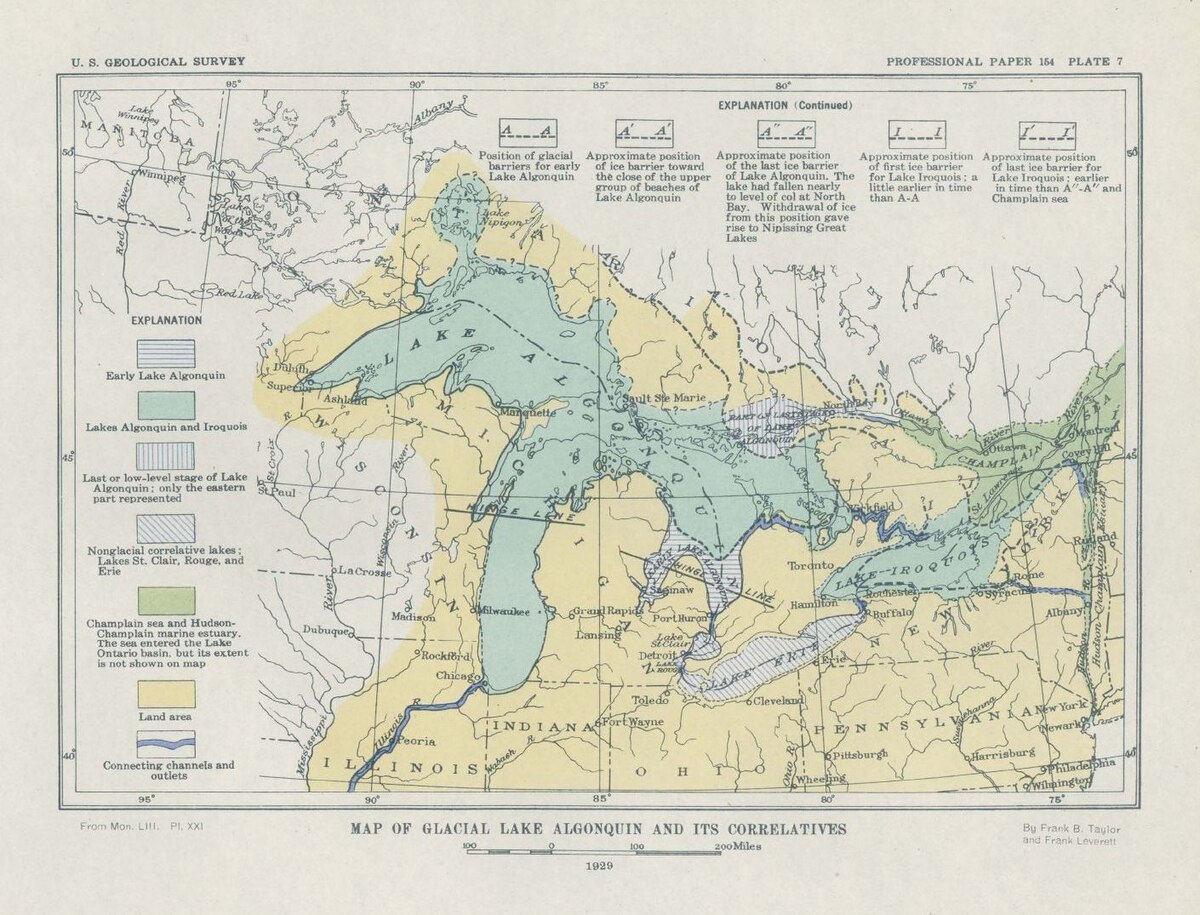

This map, from 1929, shows the extent of Lake Algonquin.

You can see that Manitoulin Island, the Bruce Peninsula, and much of the Nottawasaga watershed were covered by the water from the melted Laurentide Ice Sheet, along with the bottlenecks at what’s present-day Port Huron and Detroit/Windsor.

Click on the map for a higher resolution version.

The glacier, which reached up to 2 kilometres in height, retreated, and the meltwater formed Lake Algonquin in the basin that now holds Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, including Georgian Bay, as well as Lake Simcoe. The rivers and streams that flowed off of the newly exposed moraines carried sediment that had been ground up by the contact between the glaciers and ground. When these fast flowing rivers entered the larger Lake Algonquin, they slowed, and the sediment they carried deposited in along the shorelines, accreting in thick layers over thousands of years.

The sandy soil and large gravel deposits in the Nottawasaga watershed are the result of this gradual process of sedimentary accretion. As the glaciers melted new outlets, like the Saint Clair River, which runs from Port Huron to Lake Saint Claire and then on to the Detroit River and Lake Erie, opened up. Lake Algonquin slowly receded, in our area, to the present day shoreline of Georgian Bay, leaving behind the sandy sediment that was deposited on the bottom of the lake bed.

The decent drainage but poor nutrient retention of this soil makes it ideal for growing crops that don’t like “wet feet”, like potatoes and other root vegetables. (Alliston is known as the potato capital of Ontario, which it celebrates with its Potato Festival every August!)

Boom Cycle

Another key industry in the area was timber.

The lack of nutrient retention in the soil, with high drainage and little in the way of fine particles, like clay, to which nutrients could bind, meant that red and white pine, and oak forests were largely unchallenged by other forms of land-use, like crops or pasture, and symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi networks were crucial. These fungi connected to trees and extended outward, vastly increasing the area available for nutrient and water uptake. In return, trees provide carbohydrates to the fungi. The mycorrhiza also connected trees to other trees, facilitating cooperative transfers of nutrients between trees.

Eastern white pine in the area often exceeded 30m in height, and, due also to their light weight and resistance to warping, were ideal for use as masts, spars, and decking on British Man o’ War ships. Logs were floated down the Nottawasaga River to Georgian Bay, and then shipped across the Great Lakes to shipyards in Quebec City, Halifax, and even across the Atlantic to Liverpool and Portsmouth.

At the end of the 19th century, steel was starting to eclipse wood as the primary material for ship building, but by that time much of the large forests in the Nottawasaga watershed had already been felled.

The loss of trees, and with them the mycorrhizal fungi, exposed the underlying fragility of the ecosystem in the area. Soils lost organic matter quickly, and erosion was so severe in some places, like Edenvale, that there were near-desert conditions.

With the primary economy gone, people left the small mill towns for larger urban centres. There are still remnants of many of these ghost towns across the county.

In an effort to stabilize the soil, large tracts of land were reforested through government programs, like the County Forest system. Simcoe County became one of the largest and most active participants, marking a shift in how we think about our use, and reliance, on natural resources, from one of pure extraction, to one of stewardship and conservation.

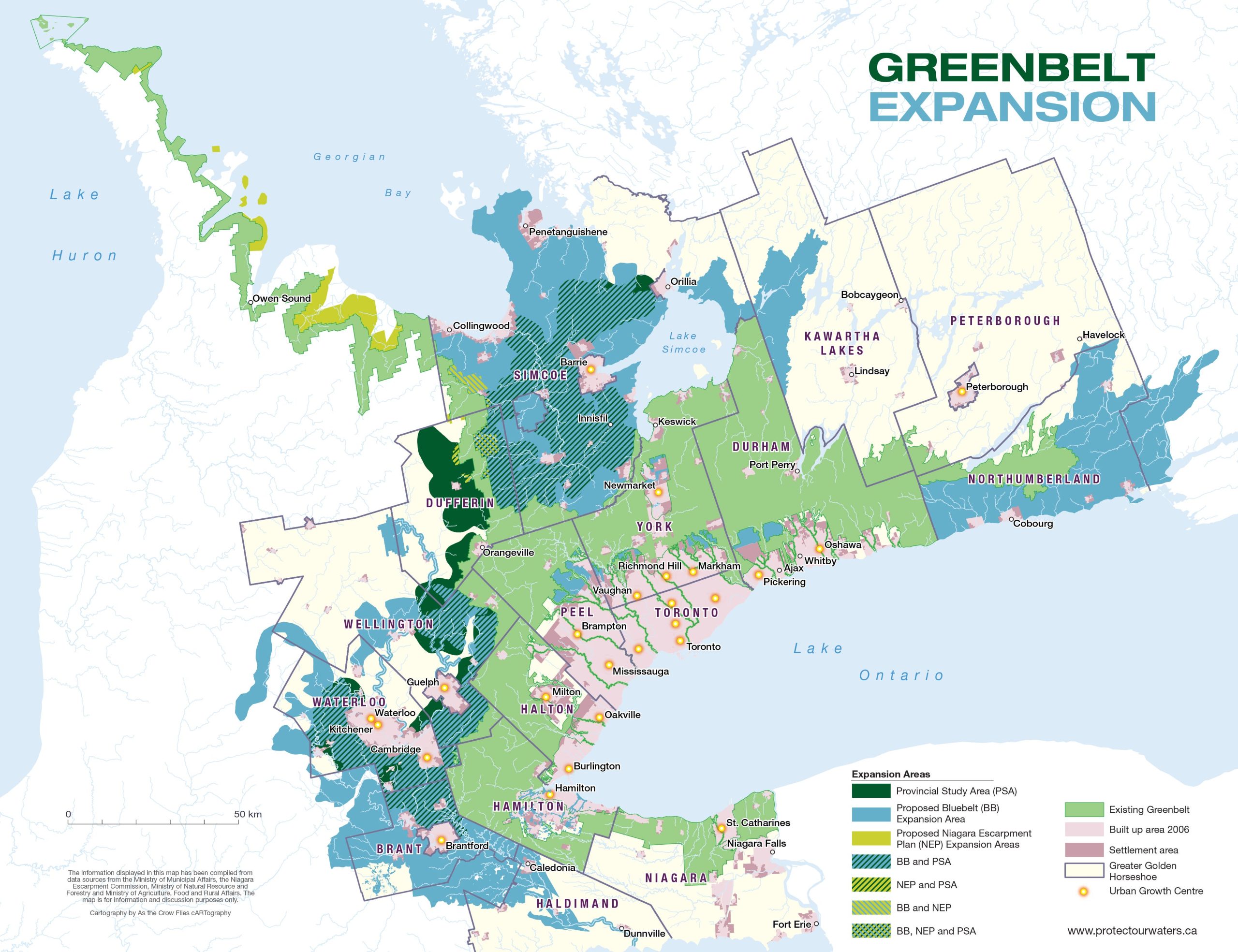

These geographic peculiarities continue to shape the economy of the watershed. The relative unsuitability of the soil for agriculture, compared to the soil of the Oak Ridges Moraine farther south (now protected by the Greenbelt), its flat terrain and proximity to the GTA, makes it attractive to developers. The siting of the Honda plant in Alliston was, in part, due to these factors, along with easy access to water and transportation lines, among others.

Simcoe County remains, for the most part, a commuter community, though, relying heavily on access to the economy of the GTA and, to a lesser extent, nearby urban centres like Barrie.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

A monthly newsletter with information on what’s happening in Simcoe County and beyond. This is the place for first-look access to community polls and Issue Briefs.

The Bluebelt

The Oak Ridges and Singhamton moraines are easy, obvious choices for Greenbelt protections. Their fertile soil is perfect for crops and pasture, and their deep aquifers provide reliable sources of water to large, nearby population centres.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the absence of these factors are, in many ways, why expanding Greenbelt protection to the Nottawasaga watershed so important.

The combination of high flow through the watershed, and the ease with which surface water passes through the shallow, sandy soil, create a hydrological system that is highly vulnerable to disturbance.

Conservation Authorities (CAs) have historically been empowered to mitigate these impacts, but recent changes by the Ford government has reduced their ability to ensure development doesn’t occur in floodplains, that proper wetland buffers are maintained, and that aquifer recharge zones are protected, to name just a few of the ways their ability to ensure we continue to have a healthy natural system has been undermined.

A couple of examples of how these changes are impacting our area:

Developments like Treetops and Belterra in the Alliston area are located above aquifers that feed the Boyne River, but the Nottawasaga River Conservation Authority (NVCA) can no longer appeal municipal approval for them.

Aggregate operations, such as the expansion of the Duntroon pit in Clearview Township, pose risks to coldwater streams and groundwater connectivity, but objections brought forward by CAs are no longer binding on approvals.

Ford maintains that these changes are necessary to ensure the housing development needed to bring more affordability to the market—remove ‘unnecessary red tape’ to speed construction up and lower costs.

Together with his dismantling of the Growth Plan, which determined where and how development occurred, Ford’s approach to addressing the housing affordability crisis seems to be enabling developers to do what they want, where they want, to the greatest degree possible.

This wide-open de-regulatory and unscientific approach flies in the face of key facts—lack of available land is not hindering housing development, and there is no need to open up areas previously protected; affordability is a bucket issue, determined not just by the cost of the house, but also by other costs, including the amount of taxes paid to maintain associated infrastructure, like roads and waste water facilities; and our exposure to risks associated with environmental change is increasing, and will continue to increase far into the future.

Conclusion

The Nottawasaga watershed, due to its natural fragility and its proximity to development pressure, is a crucial area to watch in the coming decade. The absence of a cohesive plan for the region, predicated on a recognition of its vulnerability and the need to proactively identify and protect key areas, is akin to rolling the dice with regard to whether we will have a healthy and viable ecosystem in the future.