Context

Recent moves by Ontario’s government seem likely to create conditions for a number of crises in the next few decades that, when combined, are greater than the sum of their parts. This is what’s known as a “polycrisis”, a term popularized by economic historian Adam Tooze.

Cost of living concerns, including housing, food, and energy prices, pressure on natural resources and pollution, congestion and accessibility in an economy increasingly reliant on just-in-time delivery standards, a growing infrastructure deficit combined with a lack of attention at the highest levels of government to building more efficient communities are just some of the issues coming to a head. Furthermore, the growing reality of a climate supportive regulatory framework internationally also threatens to leave behind an Ontario led by a government that continues to regress on climate action.

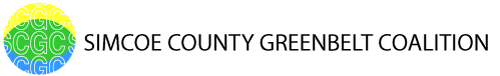

This chart from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shows the impact to GDP of delayed climate action.

The Ontario government has shown an almost antagonistic stance towards decarbonization, which places it offside both in the effort to reduce GHG pollution and in the emerging low-carbon economy.

Ironically, the government’s often stated goal of providing certainty in the market, though this tends to be directed mostly at the housing market, is undercut by its capricious decision to slash clean energy programs.

It’s widely understood that Ontario is in the midst of an affordable housing crisis. According to the province’s Housing Affordability Task Force the price of housing in Ontario has nearly tripled over the past 10 years, from $329,000 in 2011 to $923,000 in 2021, putting home ownership out of reach for many. This is an increase in the price of housing of 180%. Over the same period of time the average income in Ontario has grown by just 38%.

It’s worth noting that this government, which presumably struck the Housing Affordability Task Force for the purpose of providing solutions to the affordability crisis, recently threatened to override with the Notwithstanding Clause the labour rights of education workers seeking wage increases in line with inflation. This would have maintained downward pressure on the income of 10s of thousands of Ontarians, making it impossible for them to participate in the housing market.

Upward pressure on house prices was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, when many more wealthy property owners situated in urban areas sought to relocate to rural areas, but pressure has been building outside of that time period as well, and it is argued that this is due in large part to too few homes being built, causing a lack of supply in the market.

The Smart Prosperity Institute, who, it should be noted, is a prominent proponent of the lack of supply argument, released a report in October of 2021, almost exactly a year prior to introduction of the Act, stating that Ontario needs to build 1 million new homes over the next 10 years. This figure is extrapolated from Ministry of Finance estimates for population growth, of 2.27 million more people in Ontario, through that same period. This calculation assumes an average household size of slightly less than 2.5 people.

Proposed Changes

Introduced October 25, 2022, the More Homes Built Faster Act (the Act) is meant to achieve the goal, the government claims, of facilitating construction of 1.5 million new homes in Ontario by 2031. This is an omnibus bill, which includes changes to nine different acts, including:

- the City of Toronto Act,

- the Conservation Authorities Act,

- the Development Charges Act,

- the Municipal Act,

- the New Home Construction Licensing Act,

- the Ontario Heritage Act,

- the Ontario Land Tribunal Act,

- the Ontario Underground Infrastructure Notification System Act,

- the Planning Act, and

- the Supporting Growth and Housing in York and Durham Regions Act.

In the press release announcing the Act the government states that it will be seeking input on integrating the Provincial Policy Statement (PPS) as well as the Growth Plan into a “single, provincewide planning policy document.” While this is not part of the Act, it has been posted to the Environmental Registry for a period of public comment that closes December 30th.

Municipal Planning

The Act proposes an upper limit on the percentage of units that can be required to be affordable, at 5%, with a maximum number of years that the unit must remain affordable at 25. Putting this into context, the City of Toronto recently proposed inclusionary zoning that requires 22% of units to be affordable, with a maintenance at affordable levels of 99 years.

Units considered to be affordable are generally defined as those costing no more than 80% of the average cost of units, whether the price to purchase or rent it, in the year said unit is rented or sold. This begs the question of whether units already categorized as affordable are included in this calculation. If so, the lowering of the maximum allowed could place upward pressure on prices, including those considered affordable, due to the lower, more more diluted number of units built to meet that definition, as well as the increasing cost of market rate housing comprising the averaged figure.

In other words, this lower maximum may have the effect of diluting the number of affordable units included in the calculation, increasing the amount of what classifies as affordable.

All upper tier municipalities in the GTA, as well as Waterloo and Simcoe, will no longer have approval authority for Official Plans or their Amendments under the Planning Act. Such approvals could be appealed by residents, community organizations, as well as developers, but with their removal from the process the final approval authority goes to the Minister, where there is no possibility of appeal.

Removing planning responsibility from Regions and Simcoe County places it with, in the case of Simcoe, municipalities that are often quite small with few dedicated and knowledgeable planning or legal staff. This, paired with the potential reduction of revenue due to the changes in DCs (outlined below), as well as the potential for costs awarded by the Ontario Land Tribunal (OLT), may create a dynamic of uncertainty with respect to expertise, as well as concern regarding exposure to costs, on the part of municipalities challenging or attempting to guide development applications. This seems likely to have a chilling effect on municipal engagement in planning our communities on behalf of the public’s interest.

Affordable housing, attainable housing (for which the government says a definitional category will come in future regulation), and inclusionary zoning units will be exempt from Development Charges (DCs), Community Benefit Charges (CBCs), and parkland dedication requirements.

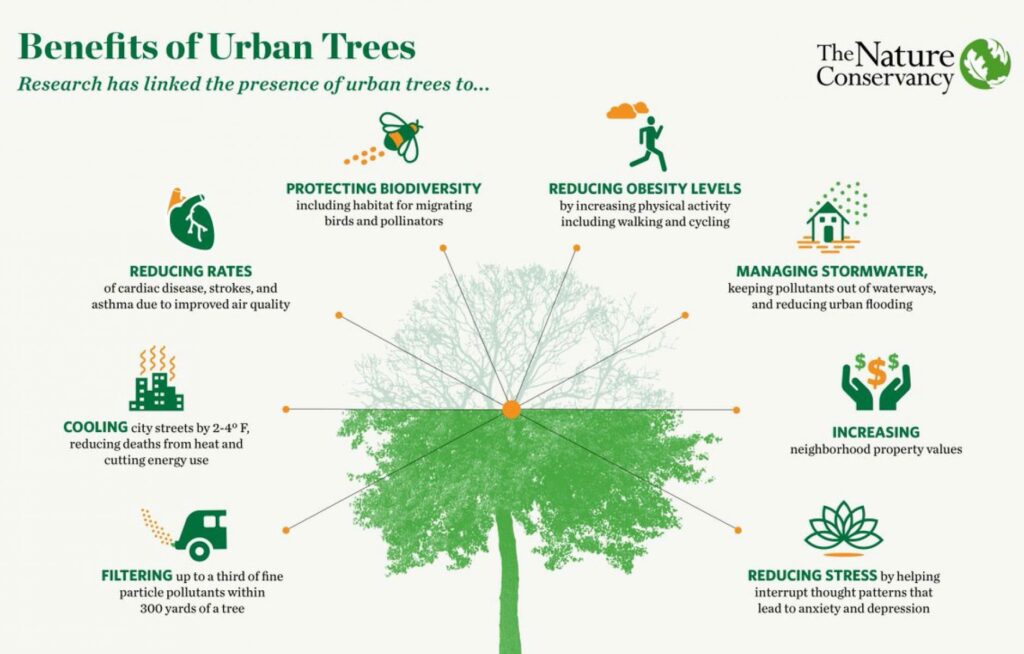

Site plan control allows municipalities to require elements, such as landscaping with trees and rain catchment features, that provide cooling, reducing reliance on air conditioners, as well as water filtration and absorption.

These are features that help mitigate the impacts of climate change, improve the quality of life for residents, and lower costs for municipalities.

All aspects of site plan control, which is a tool municipalities use to “evaluate certain site elements, such as walkways, parking areas, landscaping or exterior design on a parcel of land where development is proposed”, will be removed from all proposals that are less than 10 units. Furthermore, municipalities will be limited generally in their ability to determine architectural and landscape design details.

Limiting site plan authority is likely to result in municipalities being unable to implement climate friendly standards, such as Toronto’s Green Standard (TGS). The TGS is meant to help Toronto achieve community wide net zero carbon emissions by 2040, by “[limiting] GHG emissions from newly constructed buildings, providing electric vehicle charging in parking spaces and enhancing stormwater management and landscape requirements.” Since implemented 12 years ago the TGS has reduced Toronto’s GHG emissions by the equivalent of 52,000 cars worth every year. The landscaping component of site plan control, for example, can require trees, which give shade that helps reduce the need for air conditioning, as well as sequester carbon dioxide. Rain water gardens can help reduce flooding and improve water quality. Electric vehicle charging stations can also be mandated as part of site plan control.

“As of right” zoning would be implemented province-wide in settlement areas zoned residential with full water and sewage servicing, allowing for up to 3 units per lot with no restriction on unit size. Municipalities would be prohibited from imposing DCs, parkland, or in lieu requirements or requiring more than one parking space per additional unit.

Parks

The amount of land that can be conveyed or paid in lieu to the municipality to satisfy parkland requirements is capped at 10% for smaller developments (under 5ha) and 15% for developments larger than 5ha.

What constitutes parkland has been broadened to include privately owned accessible spaces, as well as open spaces on top of structures.

Development Charges

Any Development Charge (DC) rate increase will now be phased in over 5 years.

The historical service level for capital costs, which helps determine the rate charged, is extended from 10 to 15 years.

The effect of extending the period of time by which the rate is calculate is that it smooths the curve and, by reflecting more of the past than the present, seems likely to reduce the rate slightly.

Interest paid on DCs for rental, institutional, and non-profit housing will be capped at prime plus 1%. There will be additional inducements for purpose built rental, including a discount, freeze and deferral on DC payment over five years.

The cost of studies, including background studies, will no longer be eligible for recovery through DCs.

Municipalities will be required to spend at least 60% of DC reserve balance on priority infrastructure at the start of each year.

The ERO notice states that this is for “water, wastewater, and roads.” There is no mention of transit or other infrastructure types, except that a “regulation making authority would be provided to prescribe additional priority services…in the future.”

Transit

Municipalities will need to update zoning to set minimum heights and densities in major transit stations areas (MTSAs). Municipalities would be required to update zoning laws to allow as-of-right zoning for this increased density within one year of passage of the MTSA or Protected MTSA (PMTSA).

Capital costs that are eligible to be recovered through DCs will be determined by a longer period of time, with the historical service level extended to 15 years rather than 10 years. This would not apply to transit, however.

The separation between using a historical record for general DC rates of 15 years, from the current 10 years, and that used for transit, which remains at 10 years, has the same effect, noted above, of smoothing out and likely lowering the rate calculated over the longer time period.

In other words, car oriented service levels, and the capital costs municipalities are able to recover for them, are likely to be reduce vis transit service levels, creating further incentive for car infrastructure and sprawl at the expense of transit.

Car oriented infrastructure is far less efficient that mass transit and walkable communities. According to recent figures from the Financial Accountability Office, Ontario municipalities have an infrastructure deficit of $52 billion. Being smarter about how we use space in urban areas can increase efficiency and help reduce this backlog. Further expanding car oriented development, however, seems likely to only exacerbate the problem and further stress municipal capacity.

Conservation Authorities

The Act will repeal 36 regulations that allow Conservation Authorities (CAs) to oversee and regulate development. As a result permits from CAs will no longer be required for development authorized under the Planning Act within (formerly) regulated areas, including wetlands.

The changes mean that CA responsibilities will be narrowed to focus strictly on natural hazards and flooding, and that they will no longer be able to consider “pollution” and “conservation of land” when assessing a proposed development.

CAs are currently responsible for mitigating natural hazards and flooding risk, but, in areas such as flood risk mapping, some CAs have available mapping while others, including the NVCA and LSRCA, do not. This may have to do with a lack of resources, but narrowing their focus in this regard may not cause them to be more effective in producing results so long as municipalities, which provide funding to CAs, are constrained in their revenue generation. Municipal revenue generation may, in fact, be further constrained by the changes proposed in this Act.

Conservation of land is mentioned numerous times in the Conservation Act but never explicitly defined. Where this relates most closely to the current mandate of CAs is with respect to their ability to protect, manage and restore woodlands, wetlands, and natural habitat by placing such areas off limits to development or activity that might otherwise negatively impact them.

It’s noteworthy that when the current core mandate of CAs is considered, that they “undertake watershed-based programs to protect people and property from flooding and other natural hazards, and to conserve natural resources for economic, social and environmental benefits”, the removal of the mandate outside of the strict flooding and natural hazard responsibilities seems to either place the utility of “natural resources for economic, social, and environmental benefits” elsewhere, presumably with the development sector, or to simply negate it altogether.

One consequence of removing the conservation of land role of CAs is that, in addition maintain the integrity of natural systems they also provide recreational opportunities and programs, providing areas where the public can experience nature and partake in programming aimed at enhancing our understanding of and connection to the important roles that natural systems play in our society and economy. According to Conservation Ontario an average of 35% of CA revenue comes from fees generated through delivery of these programs, as well as other activities, such as fees from developers for permits, that also seem likely to be cut. For some CAs, such as the Grand River Conservation Authority, self generated fees make up 50% of their yearly revenue.

CAs will also be required to issue development permits for projects authorized under the province’s Community Infrastructure and Housing Accelerator, a newly created power very similar to a MZO, which grants the Minister authority to make an order, at the request of a single or lower tier municipality, expediting zoning approval so that a development may proceed. This only applies outside of the Greenbelt area.

The changes to the CAs are meant to reduce the “financial burden on developers and landowners making development-related applications and seeking permits”, a leaked document obtained by The Narwal says.

Furthermore, CAs, currently required to complete a conservation strategy and land inventory under O. Reg. 686/21, will be now required to include in that inventory a category of lands that could support housing development. This detail, which is not included in the Act, is noted on the ERO posting and outlines how such lands would be identified by consideration of “the current zoning, and the extent to which the parcel or portions of the parcel may augment natural heritage land or integrate with provincially or municipally owned land or publicly accessible lands and trails.”

Ironically, as the Narwal points out, the government itself notes in the leaked cabinet document that “the federal Parliamentary Budget Office has credited Ontario’s floodplain and hazard management policies and programs, including the role of [conservation authorities], with keeping losses associated with flooding in Ontario lower than losses seen in other Canadian provinces.”

Further, highlighting the value of what CAs do, the Insurance Bureau of Canada just released research finding that “the disclosure of natural hazard and climate risk is urgently needed in the Canadian housing market because of the increasing frequency and severity of natural disasters.” The Bureau is calling for a “climate score” metric that would indicate the exposure of a property to the risk of climate impacts.

Wetlands

Major changes will happen with how Provincially Significant Wetlands (PSWs) are assessed. Currently wetlands, when assessed (not all are), are given a score based on criteria including biological, social, hydrological, and special features. Wetlands that score above 600 combined, or above 200 on either the biological or special features component, are categorized as PSWs.

Smaller wetlands can no longer be assessed as an interconnected complex. This means that only individual wetlands at least 4 hectares in size will be assessed.

Wetlands smaller than 4 hectares were not allowed to be assessed under the previous scoring system, but they could be complexed together with other nearby smaller wetlands as a system of wetlands. This was crucial for protecting habitat for species such as the Jefferson Salamander, which prefers smaller wetlands of roughly .5 ha.

Points can no longer be awarded based on the presence of SAR. This means that wetlands that have been scored as PSWs due to the presence of SAR will now be downgraded, which means that they can be developed upon.

MNR biologists used to be responsible for rating wetlands. This responsibility is being removed and placed with municipalities.

The government plans to use offsetting so that if a wetland is built upon, a wetland elsewhere will be created. The goal is for there to be a “net gain” in natural heritage features this way. Developers who build on wetlands would pay into a fund, which would then be used to ‘compensate’ elsewhere for the loss of that wetland.

The approach misunderstands how ecosystems work, assuming them to be interchangeable blocks that can be swapped out without any loss in system function. The language of the discussion paper seems to acknowledge this, stating that “the result of an offsetting policy should be a net gain in natural heritage area and/or function.” The simple focus on natural heritage area through the use of “or” allows for the exclusion of function as a net gain requirement.

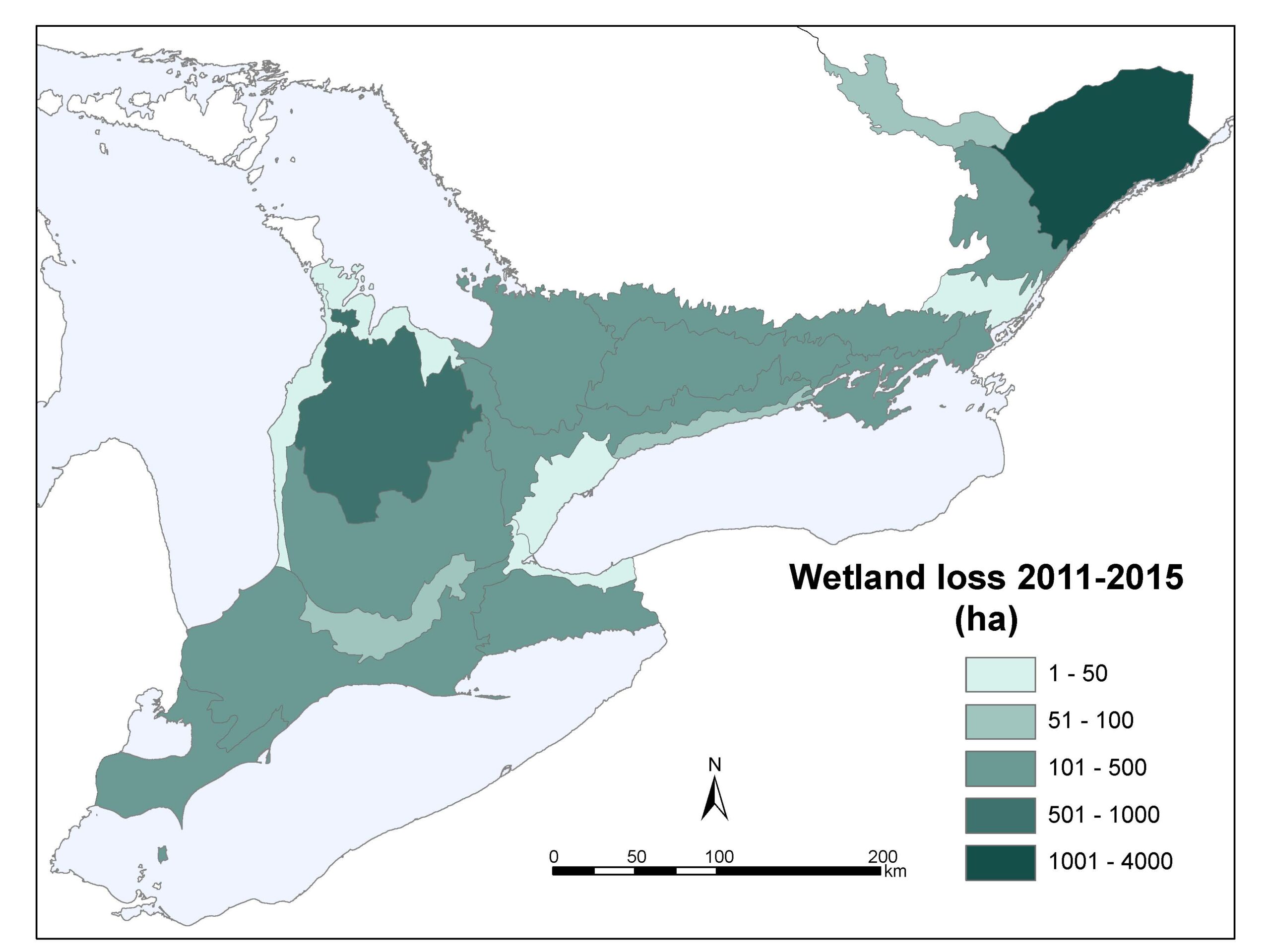

In Southern Ontario an estimated 72% of wetlands that were originally present have been lost.

Loss in particularly acute in southwestern Ontario, where about 85% of wetlands have been converted to other uses.

Source: Ontario Biodiversity Council

Public Participation

Third parties, such as residents, community organizations, and nonprofits, will no longer be allowed to appeal any Planning Act decisions. This means that only the applicant, municipality, certain public bodies, such as Indigenous communities or utility providers that have participated in the development process, and the Minister will be able to appeal decisions to the Ontario Land Tribunal.

Public meetings for subdivision plans will no longer be required.

Public participation in planning is already at a disadvantage. Members of the public have to use their own time and energy, on top of work and family duties, to participate. Developers, on other hand, are paid for their time, have access to the expertise of highly paid lawyers and planners, and can leverage relationships built with elected representatives and staff over long periods of time.

Some will argue that reducing public participation in planning will help to counter NIMBYs. Given the existing barriers it seems just as likely that wealthy and connected NIMBYs will continue to be able to prevent development they don’t desire from happening, while those with less access, namely more marginalized communities, will be left without recourse.

Additional Comments

The leaked cabinet document also provided an overview of how the Act is expected to be received by the public and other stakeholders highlights opposition is expected, noting:

“Reaction from agricultural and environmental sectors likely to be strongly negative due to potential impacts on environmental protection, increased loss and fragmentation of prime agricultural lands, subsequent negative impacts to the agri-food sector, and increased allocations of land for housing and other urban uses.”

It goes on to state that the changes are welcomed by developers:

“[The] Development sector would support simplification of the policy framework with a goal to increase housing supply, but would be concerned if changes result in delays to development applications.”

It’s worth noting that increasing housing supply can be accomplished in the Greater Toronto Hamilton Area (GTHA) within the currently designated greenlands area. Greenfield is defined by the province as “lands within settlement areas (not including rural settlements) but outside of delineated built-up areas that have been designated in an official plan for development”.

Unused greenfield in the GTHA is estimated to be 350 square kilometers.

Statistics Canada calculates the average density of Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) in Canada to be 5,385 people per square kilometer. (The downtown CMA with the highest density is Vancouver, with 18,837 residents per square kilometer. Toronto has 16,608 per square kilometer. Barrie has 2,389.) Factoring these two metrics provides a potential for 1,884,750 residents in currently designated greenfield in the GTHA.

While it is unlikely that the entirety of the unused greenfield would be developed to the density of Toronto’s downtown core, which would see 5,812,800 people accommodated, a combination of increasing densification as missing middle in currently developed areas with a similar style of development in the greenfield would allow for Ontario to easily meet projected population growth for the entire province, and this in the GTHA alone. Including development of greenfield outside of the GTHA only makes this easier.

Ultimately this makes clear that no additional land is needed to meet housing demand for the foreseeable future, and that moves to do so are the result of political choices made rather than necessity.

Affordability

The contrast between the stated goal of addressing housing affordability, the limitations placed on municipalities ability to ensure affordable housing is provided through inclusionary zoning, the hard line it is taking on wage growth in the public sector while accepting the concerns expressed by the Housing Affordability Task Force that a key part of the problem is the growing gap between house prices and income, in concert with the leaked cabinet document that notes the likelihood of widespread opposition from environmental, First Nation, and community groups indicates that this is a government that is compromised. While progressing with somewhat sound, evidence-based or well-reasoned policy in some areas, it is clear given the extent and magnitude of changes proposed here, and the degree to which they conflict with guidance and policy previously developed, that this is a government highly exposed to influence from a relatively narrow set of special interests.

This is concerning given the increasing risks that Ontario will face in a rapidly changing and uncertain world, in which costs will to a great extent be determined by how well communities and society is prepared to respond and recover prior to events and impacts occurring.

The fact that as a population grows stresses AND reliance increase on natural resources, for example, and that these resources, including a healthy Ontario-based agriculture system that is able to provide food to reduce potential shocks and price fragility associated with international supply chains, seems to be completely missing from the province’s assessment of what is needed for Ontario’s future.

The loss of farmland in Ontario at current rates may bring food sovereignty from the current ratio of roughly 2/1 food production potential to people, down to nearly 1/1 by 2046, and a loss of food sovereignty by 2055.1Food supply is calculated as the amount of people that the food an acre of farmland can produce can support, which is derived from a study by Cassidy et all (2013), titled Redefining agricultural yields: from tonnes to people nourished per hectare, and equals 2.18 people per acre. Total farmland in Ontario is calculated by MPAC at 14,154,981 acres in 2021. The rate of farmland loss is calculated by Statistics Canada’s Census of Agriculture (2021) at 116,435 acres per year.

It should be noted that climate impacts to Ontario’s agriculture productivity are anticipated to be a mix of positives and negatives. Ontario is likely to experience longer growing seasons, which will boost productivity. However there will be more droughts, pest concerns, storm damage, as well, all of which increase the instability of the system. For the chart below we maintained a business as usual scenario, leaving out the likely increase in farmland loss that will result from the changes proposed by this government, to reflect both the possible increase in productivity as well as the increased instability. To our mind instability – specifically the risk of “Black Swan” events that increased uncertainty carries – outweighs any benefit Ontario may experience. (And again, this government has stated that certainty is a goal.)

The value derived from building in a way that enhances resilience through access to a multitude of opportunities, including transportation options that enable residents to get to places of employment cheaply and reliably, or varied and diverse social connections, which greatly enhance creativity and innovation, or the co-benefits to healthcare that can be realized from being able to walk to nearby amenities, and this is to name just a few, also seems to be missing from this government’s consideration. These are the ingredients that will combine to create success in the future, but they are for the most part absent or mentioned only as window dressing.

These contradictions and counterproductive positions in the province’s policy with respect to housing and the environment illustrate the value of overarching planning.

Michael Tolensky, chief financial and operating officer at the Toronto Region Conservation Authority, told The Narwhal in a written statement. “Legislation permitting developers to profit at the expense of long-term public safety and community resiliency is purposefully shortsighted.”

Related Content

Poll – Buy Canadian

With the advent of an antagonistic, or maybe hostile, administration to the south, and the threats made by Trump to our country, this month we’re asking about the actions you’ve taken in response, and whether there are nice surprises you’ve discovered along the way?

Issue Brief: Pollution

How can something be both a pollutant and, also, not a pollutant? CO₂, it so happens, is a great place to start in understanding this paradoxical situation.

KICLEI Conspiracy Theories

This document responds to claims made by ‘KICLEI’ (Kicking International Council Out of Local Environmental Initiatives), an organization, seemingly led by a single individual, Maggie Braun, that advocates for municipalities to withdraw from global warming initiatives.

The document is lengthy. It does not have to be read in its entirety (indeed, it may be most useful as a reference document to ascertain the validity of different claims on an as-needed basis) to understand that the materials it counters are a grab-bag of claims, many rooted in conspiracy theories, many unsupported by evidence. Where attempts are made to provide sources and supporting facts, it is often in the form of links to Ms. Braun’s own work, or to other materials that remain well within the conspiracy echo chamber.

Community supported, advocacy for a safe and secure future.

Governments have failed to act to protect our communities and the futures of our children and grandchildren, and they continue to treat our environment as if it’s incidental to life, rather than a foundation for it.

We need strong community organizations to fight for our future, now more than ever.

Please consider donating to support our work. It’s people like you who make us possible.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

We send out a once-monthly newsletter full of information on what’s happening in Simcoe County and beyond, including information on how you can take action to protect the health of your community.