You’ve probably heard of sprawl. Largely residential areas that are characterized by roads, single family homes with front lawns and backyards, a garage, elementary schools located nearby, parks with playgrounds in them.

In its most extreme form, sprawl features cul-de-sacs and ‘monster’ homes – dead end roads that provide no use to anyone but those who live there, and houses characterized by ostentation, by outward appearance rather than craftsmanship or construction quality.

Sprawl, thanks in large part to the power of marketing, represents the modern version of the American dream. Bigger is better. Appearance matters more than substance. Fake it ’till you make it.

These are places where cars are needed to access basic amenities, such as grocery stores, pharmacies, doctors offices… The standard definition of urban sprawl, in keeping with the scene described above, is “the spreading of urban developments (such as houses and shopping centres) on undeveloped land near a city.”

This isn’t to say that the feature of appearance over substance isn’t based on a cold calculus, that it is absent a substantive rationale. For developers, sprawl is attractive for a reason.

Farmland surrounding built-up areas can be purchased relatively cheaply. Once it is brought within the urban boundary and approved for a subdivision, the value of that land skyrockets. And there’s a perverse incentive built into this system, which is the more land that is developed, the less land there is to build upon. As the supply of available land is constrained, the value of it grows.

There is a historical rationale for sprawl, too. Post World War II, housing development was a key economic stimulus program. Building homes provided income, which in turn went towards purchasing homes, and all of this helped to support the massive increase of the middle class.

But this was the ‘golden age’ of modernity. A time when there seemed to be no limits on what humanity was capable of.

An ad from the 1950s. Lots of lawn and green spaces held promise for those looking for a contrast from the concrete jungles of downtown.

In the aftermath of the war the vision of a utopia, with peaceful neighbourhoods, open spaces, privacy, and the ability to do as you like, carried powerful appeal.

The Costs of Sprawl

To those living in the 1950s, building in a way that spread outward, as opposed to the more compact form of city downtowns, was a no-brainer. More space meant freedom, and in particular freedom from the noise and smells and traffic – and difference, specifically racial differences – of downtowns. Suburbia meant privilege, and meant white.

The costs associated with building, and then maintaining these spread-out communities were a feature, not a bug – government largess meant jobs, and the economy was booming.

But, as we’ve since discovered, there are problems that arise when we do too much of something and don’t account for the impacts.

Fossil fuels and our heavy reliance on cars have led to the ever-growing problem of climate change, for example. With regard to sprawl, the car-centric design has made it difficult to move beyond our reliance on fossil fuels.

Additional problems, or impacts that weren’t accounted for in the decades past, have also cropped up.

Land that otherwise provides a great deal of value to the public, providing food when used for agriculture or ecosystem services, including air and water filtration and carbon sequestration, when allowed to remain in its natural state, is destroyed for a built form that is extremely expensive to maintain. The public loses the value of the services that nature provides and also has to pay for infrastructure, including roads and wastewater, which is stretched too far between houses for the tax base to sustain. Sprawl is always heavily subsidized.

The issues outlined above are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the costs of sprawl, leading many to advocate for changing the built form from sprawling outwards to one that focuses on increased density within already built-up areas.

High rises offer the promise of greatly increasing the number of people located on a given plot of land. More people equal more densely located tax revenue, which, in turn, supports greater public services, such as transit, parks, libraries and community centres.

On the surface, more high-rise buildings are a good thing. But, as is often the case, there are caveats and trade-offs that need to be understood so that we don’t repeat the mistakes of sprawl. With intensification, there can also be what is known as vertical sprawl.

Vertical sprawl refers to buildings that are, for the most part, taller than several storeys.

One of the authorities in the area, Brendan Gleeson, of the University of Melbourne in Australia, defines vertical sprawl as “the poor-quality, high-density buildings that are increasingly compacting our cities.” In other words, these are the high rises that you’ve most likely seen in cities around the world.

Problems of Vertical Sprawl

Vertical sprawl has a number of problems, some of which it shares with the more conventionally understood horizontal sprawl. Below we take a look at some of them.

Social Brittleness, or Lack of Diverse Experiences

To answer the question of what a proper urban density should be, Jane Jacobs noted that it is more a matter of performance than of abstractions about quantities of land and people. She, rightly we believe, focuses on what the purpose of the built environment should be directed towards, arguing that “densities are too low or too high when they frustrate city diversity instead of abetting it.”1Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities: Orig. Publ. 1961. Vintage Books, 1992

But why is diversity such an important thing to cities?

In horizontal sprawl, diversity is reduced by reliance on the car, primarily.

Due to the greater distance between houses, the length of roadway connecting them, as well as neighbourhood to neighbourhood, a car is needed just to access most neighbourhoods. While there are often transit options in the suburbs, these tend to be minimal, the use of which carries a degree of friction that represents a barrier to access rather than a preferred alternative to car transportation.

Further reduction in diversity occurs when cars are used as the primary mode of transportation simply due to the fact that, when inside are car, there is a greater degree of separation from the outside world. Travelling in this isolated state from the house to the grocery store and then back again removes a significant portion of interactions that could occur between those two locations.

These graphics show the possibilities for social interactions in a car dependant suburb, and a walkable community.

In the suburb, interactions are greatly reduced due to the primary role that cars play in transportation, while in a walkable community they are greatly increased due to the amount of time people spend in proximity to one another.

In a walkable community, these interactions take place in the public sphere, and can occur as happenstance. Unpredictable meetings like these present opportunities to meet and get to know people you might not otherwise come into contact with. This helps to build a sense of community by strengthening connections and shared experiences among those within it.

Furthermore, the unpredictable or happenstance nature of the meetings that occur in these settings help to ‘cross-pollinate’ experiences between different communities, leading to the creation of overarching ‘inter-communities’ that increase diversity of understandings, experiences, and opportunities. These inter-communities are particularly fertile soil for the creative and innovative activities that are so crucial to flourishing cities.

High-rises can contribute to a greater number of people within a space, increasing the interactions that occur, but there are also drawbacks that are inherent in the tall built form that can actually reduce the diversity of experience in the shared spaces surrounding them.

Above several floors, construction costs increase rapidly. This is due to simple factors, such as the increase in time that it takes for workers and materials to get to the construction site. Taller buildings require more complex engineering solutions, as well. High rises are notoriously bad at retaining energy, requiring a large amount of air conditioning in the summer and heat in the winter. These factors, and more, lead to an increase in cost for units built above several floors, making them more expensive to purchase. (We will pick up on this point and how it relates to resilience and security a little later on.)

This raises obvious concerns regarding the role of high rises in addressing the lack of affordable housing.

By limiting residency to those above a higher income than what could be met with the mid-rise form, this also acts in as an exclusionary filtering process that is similar to that observed in horizontal sprawl outlined above, albeit absent reliance (for the most part) on a car to access basic amenities. Those most likely to frequent areas surrounding the high rise, namely the residents of it, will tend to fall within a more narrowly defined social category.

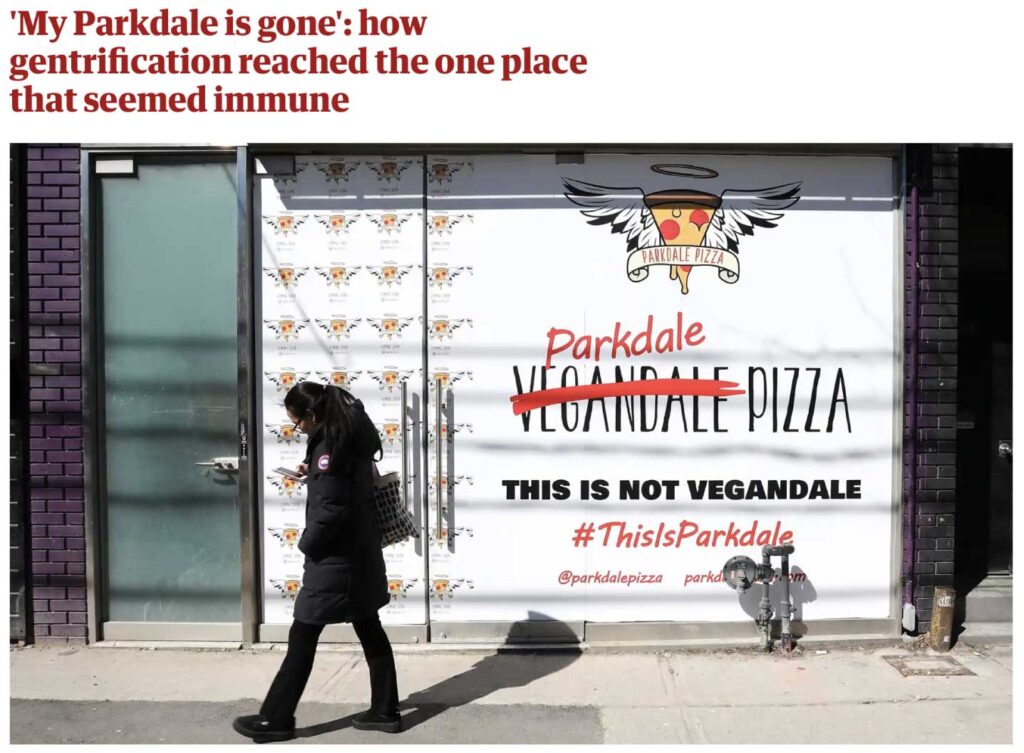

The greater costs associated with high rises tend to drive rent up in surrounding areas, contributing to gentrification, which results, first, in economic exclusion and then, second, in the corollary social exclusion.

In 2020 the Toronto neighbourhood of Parkdale experienced a take-over of sorts. A struggling neighbourhood for a long time, it had become something of a success story as residents co-created solutions to address issues associated with poverty and addictions.

When a large corporation bought up much of the housing stock, things began to change.

There are caveats to this dynamic.

First, condos can be built in such a way as to provide lower cost, more affordable housing. The Jane-Finch area in Toronto is an example of this, as are a number of apartment complexes in Barrie, and any number of cities across North America.

That said, unit size tends to be small, so that as many as possible can be packed into the floor space. Small unit size is a major reason why condos are not seen as a viable alternative to a detached or semi-detached house for many families.

Second, the gentrification effect that condos may have, even luxury ones, one surrounding rents can be ameliorated by the increase in housing supply the condo brings to the market. This, of course, is in dynamic relationship to the business case for building – demand justifies the development. If rents in the area surrounding the building offer a more attractive alternative to those offered by the building itself, the development will be in trouble. That said, there is at least short-term evidence showing that rents surrounding developments of high-rise buildings do, in certain circumstances, go down.

What these caveats suggest, however, is that, if the goal is reasonably priced, family-sized units, high-rises are unlikely to be the best option.

We tackled the issue of tall sprawl on a recent episode of our Tree Planters podcast.

It’s a great companion listen to this article, so queue it up for your next walk!

Economic Brittleness, or Lack of Diverse Opportunities

As the value of land surrounding high rises goes up, mom-and-pop stores and locally owned businesses find it increasingly difficult to maintain a presence. This is particularly true for businesses that offer unique goods. As their margins are often razor-thin, and any lag in revenue can be catastrophic.

The brittleness of this dynamic takes a few steps to understand.

As with shopping plazas associated with horizontal sprawl, it is primarily corporate businesses that have pockets deep enough to be able to afford the higher rates associated with high rises. Corporate retail is often characterized by what is known as ‘the Walmart effect’, in which employees are paid wages that are closer to the bottom end of the spectrum.

Smaller, more diverse land ownership, can help increase competition for rent, maintaining some degree of downward pressure, helping smaller businesses gain a foothold that is otherwise far more difficult for them to find. By pricing out competition, large landowners, such as those who build and operate malls or corporate plazas, are better able to monopolize rent demands.

This quote, from the excellent book, “The Gardens of Democracy”, by Eric Liu and Nick Hanauer, pushes home the point:

The market is the first force that has led to the shriveling of citizenship. The classic case is the Wal-Mart effect. A town has a Main Street of small businesses and mom-and-pop shops. The shopkeepers and their customers have relationships that are not just about economic transactions but are set in a context of family, neighborhood, people, and place. Then Wal-Mart comes to town. It offers lower prices. It offers convenience. Because of its scale and might in the marketplace, it can compensate its workers stingily and drive out competition.

The presence of Wal-Mart leads the townspeople to think of themselves primarily as consumers, and to shed other aspects of their identities, like being neighbors or parishioners or friends. As consumers first, they gravitate to the place with the lowest prices. Wal-Mart thrives. The small businesses struggle and lay off workers. They cut back on their sponsorship of tee ball, their support of the food bank. As the mom-and-pops give way to the big box, and commutes become necessary, lives become more frenetic and stressful. People see each other less often. The sense of mutual obligation that townsfolk once shared starts to evaporate. Microhabits of caring and sociability fall away. In this tableau of libertarian citizenship, market forces triumph and everyone gets better deals – yet everyone is now in many senses poorer.2Hanauer, Nick; Liu, Eric. The Gardens of Democracy. Sasquatch Books, 2011.

High rises function similarly, both with respect to residential units and associated commercial units, and, albeit in a less direct way, with respect to surrounding residential and commercial property.

Resilience and Security

Just over a month has passed since Russia invaded Ukraine. Gas prices have shot up, due to the interconnectedness of global energy markets, Russia’s large role therein, and sanctions, as well as other moves, against Russian oil.

Drivers and a man pushing a lawnmower line up at gas station in San Jose, Calif., on March 15, 1974. (AP)

Taken from NPR this article under fair-use guidelines for educational purposes.

We’ve been here before, a few times. In the 1970s, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, reduced exports in protest of the United States’ support for Israel in the Yom Kipper War, prompting shortages and lineups at gas stations.

There’s a through-line in thinking about how to address these crises, stretching from at least the 70s to today, which is that energy security, and accordingly economic security, is best ensured by increasing domestic supply and diversifying international supply.

There is little attention paid, however, to reducing the need for supply in the first place, yet this is one of the best bang-for-buck solutions available.

You will note, illustrated in the picture above, that one of the aspects of our economy that is most exposed to oil price fluctuations are internal combustion engine (ICE) automobiles, and you may be already making the connection between our reliance on automobiles and horizontal, car dependant sprawl.

Only about 12 – 30% of the energy that we put into an ICE vehicle results in movement. The rest is lost to engine and driveline inefficiencies (thermal or heat loss, for instance), as well as used for accessory purposes.

Combine this with the increased travel distance that sprawl induces, and residents are stuck between a rock and a hard place when it comes to their reliance on the car.

This high reliance creates a form of lock-in, a dependency that limits the options of residents when something like a natural disaster happens. (Or a not so natural disaster like the OPEC embargo of the 70s.) This lock-in makes people highly vulnerable to changes that are beyond their control.

For an in-depth discussion of security issues related to energy and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, listen to Ezra Klein speak with economic historian and writer, Daniel Yergin.

This is vulnerability is particularly acute when, to overcome the hazards caused by circumstances beyond their control, such as the flooding of a main road, a high degree of resources, such as energy, is required.

The same dynamic happens with tall buildings. As noted above, the taller a building is, generally, the less energy efficient it is. To overcome this inefficiency we throw energy at it, in the form of air conditioning or heating, in the form of elevators to overcome the height barrier, in the form of increasingly complex engineering solutions for waste and other challenges present.

As this just finished project in Hamilton demonstrates, high-rises can be built with a very high degree of energy efficiency. But, all else being equal, a mid-rise, built to the same specifications, is more energy efficient than a high-rise.

The key point of this dynamic, which is missing, unfortunately from the discussions of most experts, including that on the Ezra Klein Show linked to here (still a highly recommended show and episode), is that we are perfectly capable of building in a far, far more efficient manner, and that by doing so we will greatly improve the resilience of our communities and the security of our nation.

As this just finished project in Hamilton demonstrates, high-rises can be built with a very high degree of energy efficiency.

Public Dynamism Is Needed for a Healthy Society

Vertical sprawl has another characteristic that inhibits the vitality of surrounding public space, which is known as “time to street.” Put simply, this refers to the amount of time that it takes to reach the street from a residence. The higher the residence, or farther away that it is from the street, the longer it takes. This represents a barrier that inhibits propinquity in the public space surrounding the high rise.

Time to street is a characteristic that is, in some respects, shared with more conventional sprawl, though the understanding has to be reframed slightly.

Viewed as the time that it takes residents to access areas meant for public life, such as playgrounds and parks, the time that it takes for residents of horizontal sprawl to access them is clearly longer than is desirable for a vibrant public sphere.

A healthy, vibrant public space is fostered by low barriers to public activity and interaction. Benches and public furniture that encourage people to linger and inhabit a space, a diversity of activity, including walking, running, cycling, busking, eating, options for shopping, all combine to create the bustle that brings life into a space.

Accessibility to public spaces, drawing on multiple transportation options that bring people into it, as well as the function of the space itself being amenable to all, regardless of ability, age, orientation, economic or social situation, or any other attribute, is the lifeblood of a healthy society.

The architect has an opportunity to meet a small business owner, or a restaurant server, or an artist, or someone struggling with addictions, or a student… you get the point.

The value of this is that it helps reinforce and reproduce the dynamism of the public space.

When people meet others who are not from their particular walk of life, their understanding of society at large grows – a greater appreciation is developed for the needs that the student might have, such as for lower tuition rates or better access to apprenticeship opportunities, in the case of post-secondary students, or the life-affirming services associated with harm reduction for the individual struggling with addition.

Contrast this diversity of activity with the more regimented form typical of sprawl – where a walk to get groceries in a livable community comes with the likelihood of meeting a neighbour, the drive to get groceries in a suburban area encloses the individual within a metal box from their house to the store. Once at the store there may be the opportunity for interaction, but this is less than what might otherwise be since those driving to the store are from a much larger catchment area, and so also less likely to share commonalities with each other, such as their children attending the same school.

Screenshot of a streetscape photo included in Barrie’s Intensification Area Urban Design Guidelines. Note the many shops and wide pedestrian area.

What Does This Mean For Simcoe County?

Here, in Simcoe County, we see far more horizontal sprawl than vertical sprawl. Smaller communities, availability of land, proximity to Toronto for work, and the so-called ‘drive until you qualify’ effect, along with the limiting effect that the Greenbelt has upon sprawl, leading to it ‘leap frogging’ over it, combine to create welcoming conditions for urban boundary expansion.

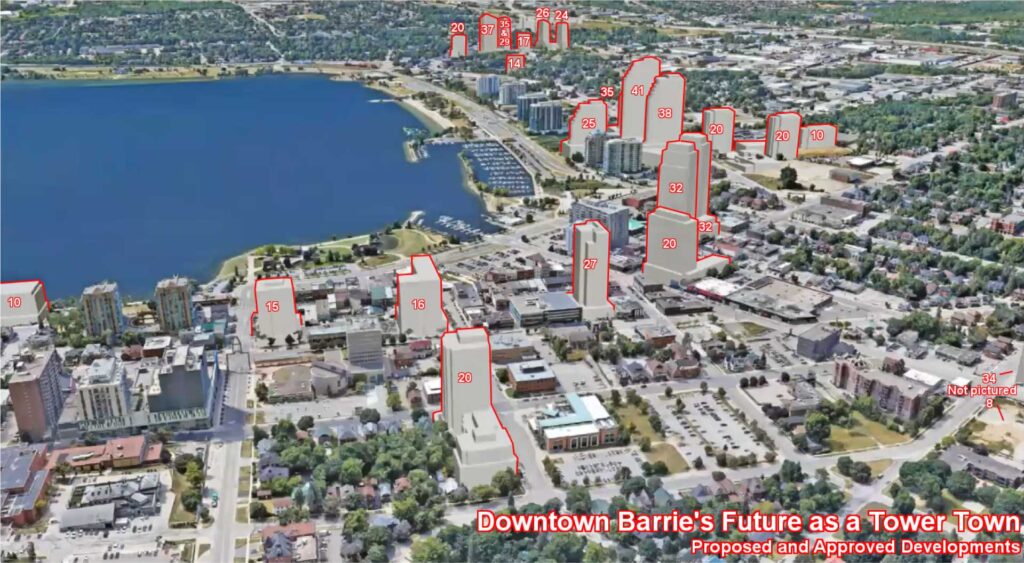

In Barrie, however, which is the largest city in the area (and, as a single tier municipality, not formerly a part of Simcoe County) there has been recognition recently of the need for intensification.

The City of Barrie’s Intensification Area Urban Design Guidelines document shows renderings with buildings no more than several storeys tall, lining streetscapes with wide pedestrian walks, shops, and lots of greenery. The guidelines state that the maximum allowable height of new buildings should be set at 8-storeys, (i) going on to note:

“generally, new buildings should have a mid-rise scale (4 to 8-storeys that promotes human- scaled development, minimizes adverse impacts on adjacent streetscapes, and provides appropriate transitions to nearby residential neighbourhoods.” (67)

Allowable heights may be increased at “Key Opportunity Sites”, but only up to at height that is equal to a 1:1 ratio with the right-of-way width, or 11 storeys, whichever is less.

This screenshot of an artistic rendering of a streetscape is taken from Barrie’s Intensification Area Urban Design Guidelines.

By far the majority of imagery used in this document highlight mid-rise development, street-level stores, and dynamic pedestrian spaces.

While there has been far more of this type of development occurring in Barrie recently, there is also a seeming disconnect between what is advocated in the guidelines, noted above, and what is occurring in the downtown area. This 3D rendering, shown by a developer during a community information session, with building storeys highlighted by Reddit user “throwawaybarrie”, shows proposals that are currently underway or that will be soon.

Rendering of the proposed developments in Barrie’s downtown, shared by a developer at a public meeting. The image has been marked up to show building heights, in floors, by Reddit user “throwawaybarrie”.

A side-note: the nearest grocery store to these buildings is an 18-minute walk.

Admittedly, guidelines are guidelines, not mandates, and council is not required to adhere to them. But the seeming divergence from a document, created by staff to help guide how the City grows, should be questioned.

Developers seek to build in a form that best maximizes their profit. For land that is cheaper, this tends to mean houses that are more spread out, with a higher premium placed on the sale of the land and associated building. With land that is more costly, such as that in more built-up areas that is closer to existing amenities, there is a need to increase the amount that the resulting building can bring in. Accordingly, a developer will want to maximize the number of units they are able to sell on the plot of land. There is a limiting factor to this, however, which is that, as noted above, the costs associated with building a high-rise increase dramatically beyond several floors.

The type of building that a developer wants in a given location, in other words, will tend to match their ability to extract a degree of profit from it. For an extremely tall building, such as those lining Billionaire’s Row in New York, the units can be sold of exorbitant prices, while in downtown Barrie, a more modest height reflects the premium a developer is able to charge for the units in the building.

Conclusion

If anything, the gap between low-rise and high-rise – the so-called “missing middle” – is an indication of a top-heavy market, wherein a relatively small number of developers, who are able to access financing for larger developments, have far more sway than smaller, more locally rooted, developers.

Funding and other tools, including target permitting changes, should be made available to help those seeking to build mid-rise developments, those who want to do the type of construction that mirrors what Barrie’s intensification guidelines set out.

The missing middle, in other words, is more about livability maximization than profit maximization.

In most of the discourse surrounding housing and affordability in Ontario, let alone Canada, much of the emphasis is on built form, with proponents arguing in favour of increased density, calling those who oppose high-rises in their neighbourhoods NIMBYs, short for “not in my backyard”, framed as a pejorative.

Those who want to keep their neighbourhood the same are, thus, against more affordable housing, and, as a recent article by a prominent planner argues, consequently also blocking progress towards a more just society.

What accusations of NIMBYism fail to adequately address, however, is a history of planning and development that has created a certain type of community. This is a community that has certain characteristics that also acts as barriers to change, and in particular to the type of change advocated by proponents of increased density. Large-scale planned development, whether horizontal or vertical, is extremely difficult to change, it is brittle in many respects, and the sociality of those inhabiting it reflects this.

It should surprise no one, then, that a built form based on single homeownership, wherein that home is the primary means of economic security and those inhabiting it see themselves mirrored in those around them, that this is a form resistant to change. What is it that the people inhabiting these spaces care for? How to conceive of and experience their ‘backyard”? What shapes and constrains a community, in other words, and how do we help an established community feel confident and safe about becoming something very different?

The key point here is that the built form enables certain types of community. Accordingly, if you want community that enhances civic spirit, that contributes to a sense of shared purpose and common goals, that helps people cut across social and economic divisions to foster greater social understands and cohesion, you need to building spaces that welcome those type of experiences. Furthermore, and continuing from the above, if you want a community that is more open to change, you need to reflect that in the built form. Allow for modularity, for creativity, for re-purposing to suit changing needs. The dynamism of such spaces has exponential returns.

One thing that needs to be addressed here is whether and how building more mid-rise than high-rise will limit urban expansion. As argued above, mid-rise development, and missing middle development generally, is more conducive to a strengthened middle class, such that there is greater social and economic equity through society.

Alternately, sprawl, both horizontal and vertical, with its higher degree of private capital, increases social and economic polarization.

It is well known that the most powerful factor in reducing population growth, a key driver behind urban expansion, is greater equity and, in particular, empowerment of women. By building spaces that prioritize equity, diversity, and inclusion, we and setting the foundations for a future that is more sustainable.

If you are to draw one conclusion or take-away from this piece – the TL;DR – it is that building, and the built environment, should reflect the needs and aspirations of a community, rather than the needs of an individual or small subset of a community.

Related Content

The Bradford Bypass – Clearing the Air

There are a lot of misconceptions, myths, and misunderstandings regarding the role that highways and cars play in our economy, and the impact they have on our environment and communities. Many of these are coming to the fore with the Bradford Bypass. Here we address some of them.

The New Growth Plan Puts Sprawl Over All

We can no longer treat land use as its own issue, nor can we always assume that growth is always a net benefit to our communities. This is simply not true. We can grow our communities in ways that provide affordable housing, protect our natural spaces and water and aspire to create healthy, vibrant centres where people can live and work.

Upper York Sewage Solution

York Region is planning to increase its capacity for wastewater treatment. The rationale is that this is required to meeting a projected increase of roughly 150,000 in population by 2031.

A key aspect of this project that is important to recognize that it is more than the sum of its parts. The EA for the project, on its own, does not capture the impacts the wastewater treatment facility will have on the region.