The Bradford Bypass - Clearing the Air

There are a lot of misconceptions, myths, and misunderstandings regarding the role that highways and cars play in our economy, and the impact they have on our environment and communities. Many of these are coming to the fore with the Bradford Bypass. Here we address some of them.

Municipalities in the Lake Simcoe region, including just recently Barrie, are being asked to weigh in on the Bradford Bypass, a proposed highway that would run just north of Bradford, through the Greenbelt and Holland Marsh, to connect the 404 and 400 highways.

There have been a number of statements and assertions made in support of the project. Environmental organizations, including ours, and community members argue, however, that these points either don’t hold water, or that they represent ways of planning that are outdated in an age of environmental crises.

Let’s look at some of the main arguments supporters make and why they are wrong.

Argument 1: It isn't our problem

This argument is tied in with jurisdictional concerns, but there’s an important distinction to be made between the political boundary, on the one hand, and the impact of the project on the environment, on the other.

Let’s start with the jurisdictional concerns and then move on to the environmental impact concerns.

It’s a well established political norm to work across political boundaries to address issues that may have an environmental impact. Perhaps the most prominent example of this is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which has members from 195 nations. A less well known, but much older, example is the International Joint Commission, which was established in 1909 and works to address issues affecting the quality of water along the border between Canada and the United States. Much of The Great Lakes are overseen by this body.

Environmental impacts, we now understand very well, are often difficult to contain, particularly when they occur in the fluid dynamics of air and water, and so work across jurisdictional boundaries is crucial to address them.

A more local example of the importance of working across political boundaries to address environmental impacts is our Conservation Authorities, which are established according to the natural boundaries of watersheds, and so attempt to capture, in a sense, the environmental impact of our actions.

Now, to address the more localized impacts and whether a highway in Bradford will affect those of us living in Barrie.

Part of the rationale for building the highway is to accommodate the projected population growth in Simcoe County, not simply the growth that is expected in the Bradford area. The vehicle trips this project is intended to accommodate come, in large part, from surrounding municipalities, including Innisfil and Barrie, which sends commuters down the 400 highway toward Toronto and the GTA.

(As an aside, there have also been a number of comments made, including by the mayor of Innisfil, that discount the voices of those who don’t live in the immediate area. These voices come from communities the Bypass is meant to serve. Accordingly, the decision of whether to continue to pour public funds into highways and car-centric development will impact how communities are shaped in these surrounding areas, determining, for example, whether there’s money available to ensure residents there have access to well-connected transit and/or safe cycling and walking routes.)

Argument 2: A new highway will reduce emissions and help combat climate change

The notion that a highway will reduce emissions seems to be based on the idea that vehicles stuck in traffic emit more greenhouse gases than those not stuck in traffic.

On the surface this seems like a reasonable argument, but the data, and experience, doesn’t back it up. Below, we cover two of the most glaring reasons why this doesn’t hold.

One thing we know for SURE — building & widening highways ALWAYS succeeds in helping sell more cars, gas & suburban sprawl; burning more public budgets; & increasing GHG emissions. So if THOSE are your goals, it’s the perfect thing to do.

— Brent Toderian (@BrentToderian) February 12, 2021

Just don’t expect it to reduce traffic. pic.twitter.com/ZjnwHyHprB

Induced Demand

As more roads and highways are built, the consequence is more use of roads and highways – one begets the other. As roads and highways make land more accessible commercial centres are built at interchanges and residential areas are developed, and with this more vehicles flood into the extra capacity that has been created.

This phenomenon is known as “induced demand,” and it has been shown to happen over and over again when roads are expanded and highways built to “ease congestion.”

(Who doesn’t want congestion eased? The problem is that this just doesn’t accomplish that. Want to spend less time stuck in your car? Stop building roads as the primary way of getting everywhere.)

Evidence shows that the eventual result of these efforts to ease congestion is always more congestion. (Some of you may have also noticed that increased demand is exactly the business case proponents are making for the highway, so there’s that, too.)

The Free Burger Analogy

Here’s a great analogy of that helps explain induced demand.

Imagine that 10,000 free hamburgers are placed in the central square of a city, with a lead time of preparation and notice given to the public (as would happen with building a highway).

What would happen?

People would come and eat the hamburgers, and soon there would be none left.

There would soon be a problem, however.

More people would come to get the free meals than what’s available.

The solution?

Put out more free burgers. And so on and so forth.

Alternatives, such as the taco joint down the street, would be decimated.

This is exactly what happens to public transit and walkable communities every time we build more highways and car-centred sprawl.

See the original post here.

There’s also this explainer, but it doesn’t include hamburgers… you’ve been forewarned.

Idling cars produce more GHG emissions than moving cars

Studies show that this is a myth. Emissions are actually strongly correlated with the distance and rate or speed of travel, and weakly correlated with the level of congestion.1Congestion and emissions mitigation: A comparison of capacity, demand, and vehicle based strategies

Vehicles travelling at higher speeds emit more GHGs than those moving at lower speeds. Building more highways and inducing more people to travel at higher speeds leads to higher emissions. This is compounded by induced demand, which sees more vehicular traffic occur.

There are further reasons why this argument is no longer valid.

Vehicles sold today are increasingly equipped with kill switches that turn off the engine when the car is stationary. Accordingly, vehicles stopped in traffic are producing very little, if any, GHG emissions. Further, and this is linked to a lengthy explanation below, government policy is increasingly geared towards promotion of a modal shift from vehicles with internal combustion engines to those with electric drives. In both cases emissions from idling, even without the research noted above, is made moot.

Argument 3: We need highways to prepare for growth

It is true that we need to plan and prepare to meet increased growth. The question that needs to be answered, however, is how can we do this in a way that is efficient? In other words, how do we make the best use of the resources available to us? (More people means more pressure on resources. If we plan prudently we can ensure that that pressure is lessened, so that our communities can continue to rely on clean water, vibrant green spaces, and fertile farmland.)

Here again highways fail to make the grade.

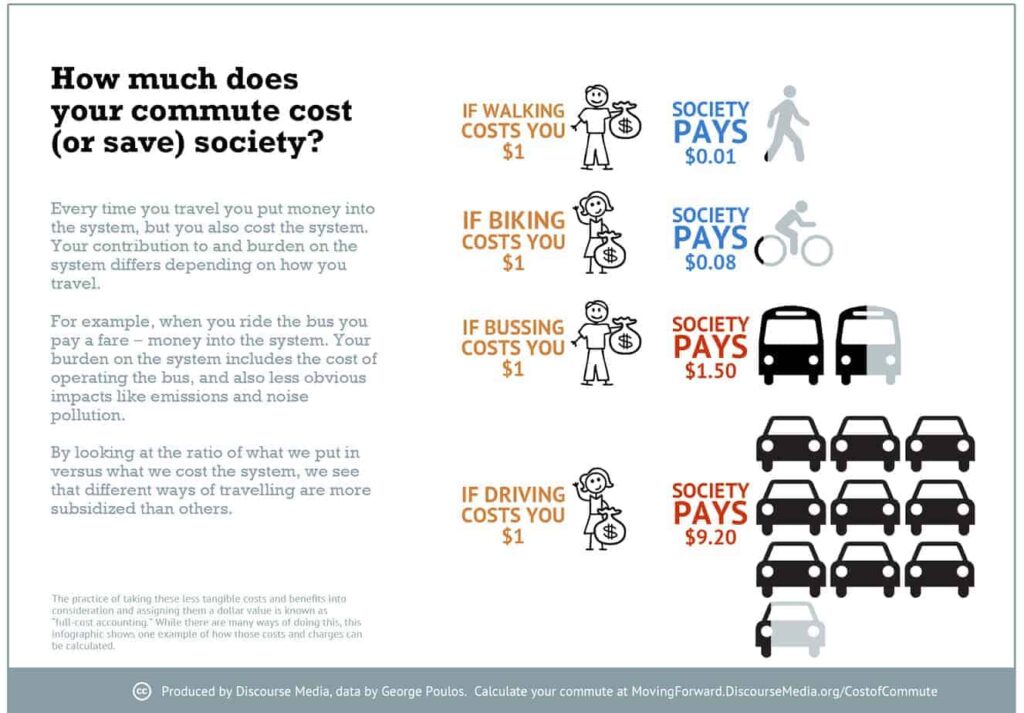

Highways, most often used to transport a single person per car, are possibly the least efficient option for transportation.

This lack of efficiency – the cost that cars have – has real impacts on our society, including on municipal budgets.

There is currently a multi-billion dollar infrastructure deficit in Ontario, much of it related to roads. This is a cost borne by the taxpayer.2Canadian Infrastructure Report Card

(Roads and highways, if you think about it, are basically subsidies to developers, since they cost more for the public to maintain than they return to the economy when compared with alternatives such as complete communities linked by rail. See the graphic below for more on this.)

If we are serious about preparing to accommodate the projected growth in population that our region will see in the coming decades, we need to be looking at options that are efficient, that give the best return to the taxpayer, that protect the crucial resources our communities rely on, such as wetlands that filter water, forests that provide habitat for wildlife and filter air of pollutants, and farmland that provides us with healthy, local food.

This last point, the value of supporting a local food ecosystem, is particularly important given the price shocks we have been exposed to with a stretched out global supply chain. It’s also particularly salient given the area this highway will impact, the Holland Marsh or the “Salad belt”, which has some of Ontario’s most valuable, productive farmland.

The increasing cost of food is something we’ve all experienced over the course of the pandemic, and it’s a factor that will only increase in volatility as climate change increasingly impacts agricultural areas in closer to the equator. The US breadbasket, for example, and the aquifer it relies upon, the Ogallala Aquifer, the country’s largest, is facing serious risks due to increased temperatures from climate change.

Congestion is a drag

This argument is pretty straight forward – the more time people and goods spend stuck in traffic, the more money and potential productivity our economy loses.

Even if you’ve entirely bought into the notion that the best economy is the most productive economy (there is a growing chorus from economists and activists taking issue with this notion, pointing out that the goal of our economy should be to promote the health and well-being of citizens, rather than the simplistic, never-ending pursuit of GDP growth, and the corollary impacts it has on the health of the environment, as well on our social and mental health) the straight forward solution to this would be to plan for strongly connected, complete communities.

These are communities in which efficient transportation is prioritized, enabling people to get to and from work easily and without relying on cars. (Cars and their operation, after all, suck up a lot of financial resources that could otherwise be circulating within the local economy.)

Argument 4: We will all be driving electric vehicles soon, so we don't need to worry about emissions

There are other ways in which our car-centric planning, which highways perpetuate, is creating problems. Many jurisdictions will be hard-pressed to meet GHG emissions targets due to the over-reliance on cars that our communities have – a long history of building for cars rather than for people.

A key method for achieving a large portion of reductions, though even with this their targets, for the most part, are still badly missed, is encouraging a modal shift in transportation from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles.

A reliance on EVs for emission reductions raises several red flags, however. EVs are an important tool in transitioning to an economy that is in line with what’s needed to ensure a safe planet for our children and grandchildren, but they are just that, a tool to transition.

The more that we rely on EVs the greater the risk we build into our strategies for reducing GHG emissions, and, importantly, our environmental and social impact.

Again, this is one of those issues that on the surface appears to be a no-brainer, but it’s exactly for this reason that it’s problematic.

Phantom reductions

EVs, on their own, represent a stark contrast with the heavy impact we now know is associated with cars using internal combustion engines. Run an EV in a garage with the door closed and you don’t have any problems.

Where things start to get tricky, however, is when you consider the complete cost of the EV, including the source of the power an EV is using and the materials required for its components.

The electricity used to power an EV may not be from a renewable source. Ontario currently generates part of its power with natural gas. Natural gas is a source of methane, which, gram for gram, is one of the most potent GHGs.

Most of the natural gas that we use in Ontario, and this goes for home heating and cooking as well, comes from Alberta and BC, where fracking is used to extract it from the ground. Methane is released in the process of fracking as well, along with a number of other highly damaging environmental impacts. There is also an increasingly large liability of abandoned wells, which the public is likely on the hook for.

“Most of the natural gas that we use in Ontario, and this goes for home heating and cooking as well, comes from Alberta and BC, where fracking is used to extract it from the ground.”

The important point here, however, isn’t necessarily the type of power that is being used, but rather the ability of governments to effectively control the type of power. Relying on EVs for emissions reductions may be an effective political win locally, but without an ability to determine where the power is coming from, governments are taking a risk that emissions will simply be displaced from one jurisdiction to another.

The control, or lack thereof, that local governments have over the power generation mix pales in comparison to their control over where the materials used in EVs come from.

This is where risk starts to increase exponentially. Emissions reductions can be claimed locally, but what in fact has happened is they have been displaced elsewhere. This opens the door to a race-to-the-bottom scenario where some jurisdictions are forced to compete for emissions, becoming a dumping ground for the reductions gained in wealthier areas. This dynamic is already occurring, with certain parts of the world, largely in the global south, competing to attract economic investment by slashing environmental regulations. (And here in Ontario, the provincial government’s COVID economic recovery strategy has been largely based on skirting environmental regulation in order to push forward with developments.)

Perpetuating colonialism

The components used in batteries come, in large part, from countries in the global south.

Lithium is largely found in arid regions of Bolivia and Chile. Mining lithium requires huge amounts of water, as well as sulphuric acid, and the use of these resources is wreaking havoc on local environments.

Cobalt is mostly mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where child labour is often implicated and a near complete lack of environmental regulation and protections exists.

While we don’t use power generated in these areas, we are nevertheless displacing a huge environmental burden onto them with our efforts to reduce our emissions through our reliance on EVs.

This is not only an environmental issue, it is also, and perhaps more importantly, a social justice issue.

Those of us who are able to afford an EV are far more responsible for climate change than those who live in these areas of the world.

Placing the burden of our emissions reductions on those who are not responsible for climate change represents a profound injustice. This is a continuance of colonialism, whereby the externalities of our economic and social activity are dumped, effectively, onto regions and people who don’t have the means to defend themselves, people and communities who are already at a disadvantage due to centuries of the very same colonialism, the extraction of value, that has so greatly benefited the global north. Such a dynamic is a taking over of their environment, of their communities and their farmland and their rivers and streams and aquifers, for our purposes. To the extent that we rely on solutions with a long tail, whereby the impacts are felt in ways that we do not have to directly grapple with, we assume an increased risk of wrong and error associated with that activity.

Additional costs

Recycling of the materials associated with EVs represents another challenge that municipalities will have to face.

While current lithium-ion batteries are difficult to fully recycling, new solid state batteries anticipated to come online soon should be easier. This is a double-edged sword, however, meaning that while the impact to the global south may be somewhat reduced (see induced demand for why this won’t solve the problems here), it will make it more likely that this is a service that local governments are expected to support.

There are also factors that many governments don’t seem to be including yet in their future estimation of infrastructure costs, namely the added weight associated with EVs and the impact that will have on roads.3Vehicle Weight vs Road Damage Levels

This means that as more EVs use our roads, we will need to increase road weight tolerances, which means we’ll be increasing the amount of aggregate that we need to mine or recycle. All of this increases the amount of money that we need to spend on car infrastructure.

Conclusion

We really need to be planning now for the communities that we want in twenty, thirty, fifty years from now. We need to do this in a way that preserves and enhances the natural resources that we have, so that our economy can continue to flourish for our children and grandchildren, and not be depleted in the short-term here and now.

Build within the urban boundary for density so that people can access groceries and workplaces and schools and parks by walking and cycling. This has benefits for our health and wellbeing as well as for our pocketbooks freeing up money in the household budget, otherwise spent on cars, that can instead be spent on quality time with family and friends.

Freeing us up from the expense of owning and operating a car – the second-biggest expense in Canadian households – also makes it possible to transition to a four-day work week, further supporting the health and wellbeing of citizens and helping to reduce the impact that our economy has on the environment.

Build high-speed rail between urban hubs so that we don’t need highways, and situate neighbourhood car-sharing nodes, so residents can access efficient and affordable personal transportation options if required.

All of this, compared to the costs associated with building highways and pouring money into mitigation the costs that will follow them, is in fact easy. All it requires is vision and leadership.

How Can You Get Involved?

- Links and resources are available here: linktr.ee/stopthebradfordbypass

- Visit our Bradford Bypass issues page to learn more about the project.

- Donate to help us fight this highway! See how some of our efforts have paid off in a Toronto Star/National Observer investigation into the highway.

Related Content

The Bradford Bypass – Clearing the Air

There are a lot of misconceptions, myths, and misunderstandings regarding the role that highways and cars play in our economy, and the impact they have on our environment and communities. Many of these are coming to the fore with the Bradford Bypass. Here we address some of them.

Bradford Bypass

The provincial government is proposing a highway that would connect the 404 with the 400. The proposed route passes along the northern edge of Bradford, and through portions of the Holland Marsh.

Ontario’s new highways, with guest Laura Bowman of Ecojustice

On this episode of the Tree Planters Podcast we talk with Laura Bowman, of Ecojustice, about the province’s plans to build new highways in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA).