Getting to Know Us: Protecting the Environment

This is part two of three “getting to know us” posts. You can find part one, which focuses on the benefits of smart planning, here.

In this post, we continue with outlining our “two sides of the coin” approach, which we use to push for what are known as “co-benefits”.

Where, in the first post we looked, as noted above, at the benefits of planning our communities in a way that maximizes their potential, in this post, we look at the flip side of the coin, which is the environmental benefits that smarter planning provides.

Climate and Environment

In the previous post, we discussed the benefits to the taxpayer of more efficient land-use planning.

This week we are looking at the other side of that coin, which is the environmental benefits that better planning has.

This is a theme that you will see throughout our advocacy work, that prudent economic stewardship often goes hand in hand with environmental protection. The two share a common principle, which is that more and better information leads to optimal outcomes.

Car Dependancy

In North America, we tend to build communities in a way that requires people to use their cars, whether to access basic amenities, such as groceries, or to commute to work. This traps us in a high-impact lifestyle, which is both carbon intensive and incredibly expensive for municipalities (as we discussed last week).

(A study by the Canadian Automobile Association estimates that, on average, Canadians spend about $10,000 per year, per vehicle, on their cars. The study was done several years ago, so, after factoring in inflation, it’s likely much higher now. This is a high price to pay for a depreciating asset that is parked 95% of the time.)

These data show the role transportation plays in contributing to climate change. Next to the oil and gas sector, transportation accounts for the highest amount of GHG emissions in Canada, at 28% and 22% respectively.

Out of that 22% portion related to transportation, passenger transportation (our cars, SUVs, pickup trucks and all that) makes up nearly 60% of emissions. The remaining 40% comes from freight, which includes heavy trucks, rail, and air transport.

Now, there may be some good news on this front, but it’s fraught with potential moral hazard.

The transition to electric vehicles can make a significant difference in carbon emissions if the source of power used to charge their batteries is clean.

Ontario has a mixed record on this front. While the closure of the coal-fired power plants greatly reduced our emissions (and greatly improved our air quality and health), emissions have since been creeping up.

The current government plans to increase use of natural gas for power generation, setting the stage for GHG emissions from Ontario’s power generation to increase by 400% over the next two decades.

Powering EVs in this way doesn’t effectively reduce emissions, particularly when the methane associated with natural gas production is factored in. (Typically this is pretty significant, equalling the climate warming potential of coal. There are also additional impacts associated with EV production.)

We all like our cars, but we also like having a healthy environment. (This is part of the fascinating duality of the suburban experience. Many people prefer living in suburbs due to its association with more green spaces, its distance from pollution hot spots such as highways and industrial areas. But, this lifestyle also generates those same problems, only in a way that isn’t as apparent.)

By continuing to promote car dependant development as the way forward, and doubling down on car infrastructure such as highways, we risk vastly increasing the amount of carbon spewing into the atmosphere at precisely the time when it’s most dangerous.

Many governments, however, whether municipal, provincial, or federal, are relying heavily on electric vehicles to achieve net-zero goals.

EVs absolutely are a key tool in efforts to combat climate change, but to really put ourselves on a sustainable path forward we need to get back to building communities for people rather than for cars. Building human centred spaces both reduces the tax burden, as covered in our previous email, and contributes to progress on climate change as well as protection of green spaces, which is what we turn to next.

Farmland

We saw during COVID, and we continue to see, the impacts that long supply chains can have on prices, including, particularly, with the cost of groceries.

There can be a lot of benefit to global supply chains. Markets have more opportunity to find efficiencies, such that products are produced more cheaply. (There are often problems with this as well, including the costs of cheap production taking the form of pollution and exploitation of workers, but that is a topic for another time.)

One example of how global supply chains can be beneficial is shown in a comparison of GHGs associated with the supply of New Zealand apples compared to apples from domestic or near-domestic producers. Due to the different types of transportation used in bring the goods to market, with the apples from NZ being shipped in a cooler ship able to hold several million items, while domestic apples are shipped via semi-truck, able to hold only a few tens of thousands of items, the goods transported from the other side of the world can be less carbon intensive than those produced in our backyard.

But these long supply chains are also exposed to more risk, where problems at one link can lead to a failure of the entire chain.

Resilience, a key term you’re likely to see repeated in our work, requires that there are options in the event that something goes wrong, and that these options can be used to withstand shocks or unforeseen changes and help to maintain a degree of normalcy.

Our farmers and local agricultural systems play a key role in providing this resilience, particularly with respect to the supply of food.

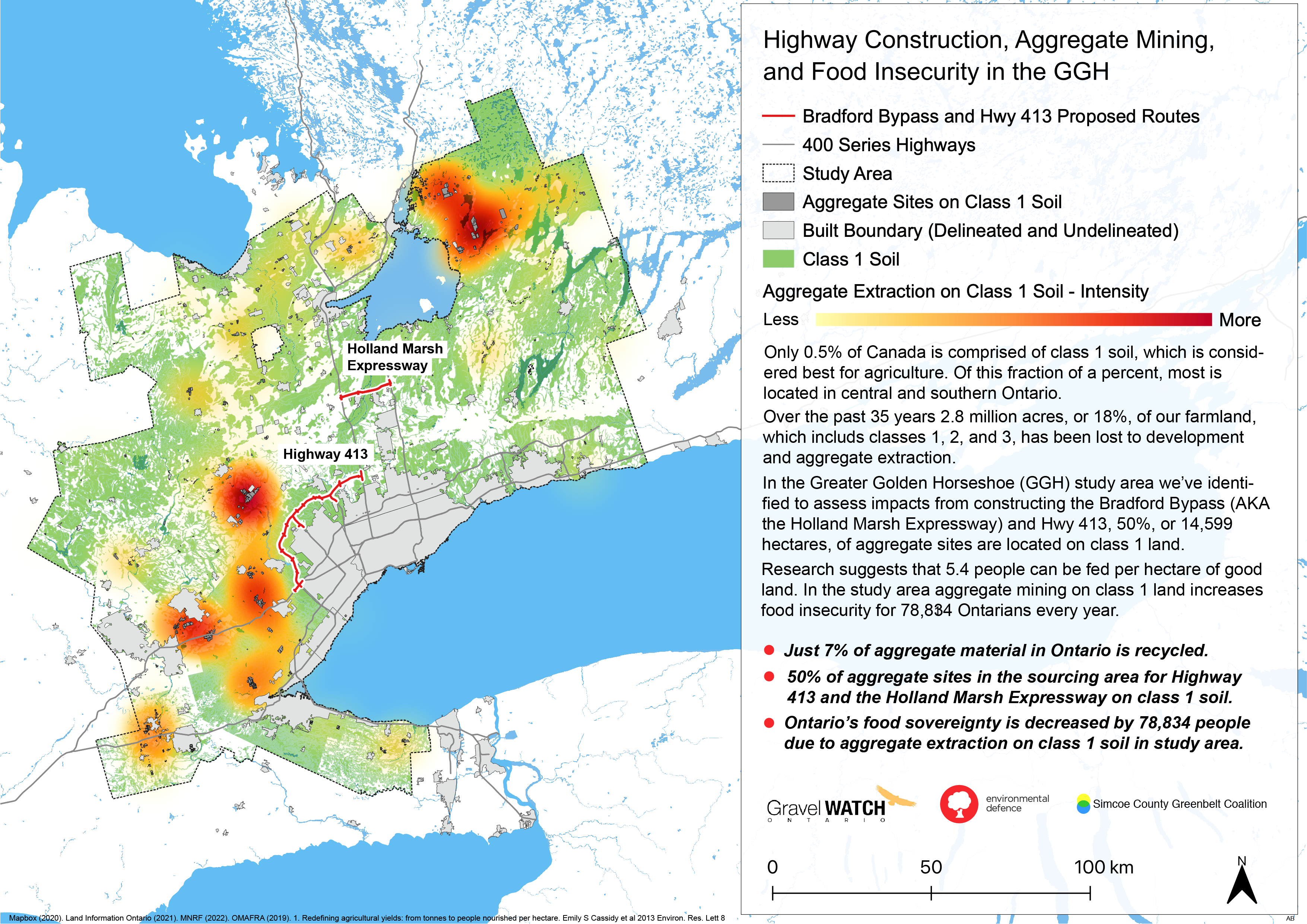

Over the past three decades, however, Ontario has lost 2.8 millions acres, or 18%, of its prime agricultural land. Currently, we continue to lose 319 acres every day. At this rate, according to our own research, Ontario will loss food sovereignty, or our ability to feed our population with our own food, by mid- this century.

These data indicate that Ontario’s food sovereignty, or its ability to grow enough food for its own population, may be threatened if current trends in farmland loss aren’t addressed.

The measure of Food Production is drawn from calculations of the number of people fed per hectare in the U.S. under current dietary customs.1Cassidy, Emily S., Paul C. West, James S. Gerber, and Jonathan A. Foley. “Redefining Agricultural Yields: From Tonnes to People Nourished per Hectare.” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 8, no. 3, 2013, p. 034015. IOP Publishing, doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034015. This figure, which is 5.4 people per hectare of good farmland, is roughly a third of what it could be due to the role of meat, which consumes large amounts of energy compared to what it provides, in the North American diet.

The Twined Roles of Sprawl and Aggregate in Farmland Loss

As we’ve alluded to, one of the main drivers of farmland loss is sprawl. But there’s another culprit, intertwined with sprawl, behind farmland loss.

Aggregate mining is an activity that plays a crucial role in our economy. It provides the raw materials for roads, highways, houses and other buildings.

Aggregate itself isn’t necessarily a large contributor to farmland loss, but it is significant, and the industry has skin in the game, as it where, in promoting the use of its product when it comes to development.

A recent mapping project we did, in partnership with Environmental Defence and Gravel Watch Ontario, shows how aggregate operations impact Class 1 soil in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, as well as in central Ontario.

This mapping provides a sense of where aggregate activity is impacting Ontario’s agricultural potential.

The study area noted on the map was for aggregate sourcing related to construction of Highway 413 and the Bradford Bypass.

As population and resource demand increase pressure on the land, it becomes more important to be prudent and efficient with the way that we use it.

The Economy and the Environment Are Not Mutually Exclusive

The goal of this piece and its predecessor, and of our work generally, is to drive home the message that a healthy environment is the foundation of a healthy economy.

It is true that at certain stages of economic development, resource depletion may be unavoidable.

But an economy that relies on a non-renewable resource, or over-extracts a renewable resource, fails once that resource becomes exhausted.

Related Content

Vertical Sprawl

By building spaces that prioritize equity, diversity, and inclusion, we are setting the foundations for a future that is more sustainable. Sprawl, including vertical sprawl, is not the right way to do this.

The Bradford Bypass – Clearing the Air

There are a lot of misconceptions, myths, and misunderstandings regarding the role that highways and cars play in our economy, and the impact they have on our environment and communities. Many of these are coming to the fore with the Bradford Bypass. Here we address some of them.

The New Growth Plan Puts Sprawl Over All

We can no longer treat land use as its own issue, nor can we always assume that growth is always a net benefit to our communities. This is simply not true. We can grow our communities in ways that provide affordable housing, protect our natural spaces and water and aspire to create healthy, vibrant centres where people can live and work.

Upper York Sewage Solution

York Region is planning to increase its capacity for wastewater treatment. The rationale is that this is required to meeting a projected increase of roughly 150,000 in population by 2031.

A key aspect of this project that is important to recognize that it is more than the sum of its parts. The EA for the project, on its own, does not capture the impacts the wastewater treatment facility will have on the region.

Bradford Bypass

The provincial government is proposing a highway that would connect the 404 with the 400. The proposed route passes along the northern edge of Bradford, and through portions of the Holland Marsh.